TEACHERS IN THE 19th CENTURY

This article is a brief overview of the developments of the training of teachers in the first half of the 19th century as they relate to the Pembrey Copperworks School.

Discarded Footmen

At the beginning of the 19th century the status of the teacher was extremely low. The well-known words of Lord Macaulay are harsh but probably largely true of most, when he described the schoolmaster as: “the refuse of all other callings, discarded footmen, ruined pedlars, men who cannot work a sum in the rule of three, men who do not know whether the earth is a sphere or a cube, men who do not know whether Jerusalem is in Asia or America. And to such men, men to whom none of us would entrust the key of his cellar, we have entrusted the mind of the rising generation, and with the mind of the rising generation, the freedom, the happiness, the glory of our country.”

As an occupation it was precarious and uncertain and full of largely untrained and unskilled people. Teaching was often the job of single women who normally left when they got married. When the first headteacher of the Pembrey Copperworks Boys’ School, Richard Williams, left to become the postmaster in Burry Port it was no doubt to a ‘superior’ occupation. It would not be uncommon for the teacher of a school to be in charge of a hundred children with little help and also do the job of the caretaker and handyman. Little attracted someone to teaching except to make a contribution to the education of the poor. For it was said of the teacher that his income was not much more than that of an agricultural labourer, and “very rarely equal to that of a moderately skilled mechanic”.

In the opening passages of ‘Hard Times’, Charles Dickens has school board Superintendent Thomas Gradgrind berating a newly trained teacher: “Now, what I want is Facts. Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else, and root out everything else”. At this time a certificated headteacher might, with a combination of Government grant topped up by the school management, earn up to around £60 plus a house. Women earned two thirds of that. Indeed, those who wanted to improve education and make it available to the ordinary working classes and the poor realised that the key was to train teachers. There were examples of teachers getting together for mutual self-improvement, but it was the introduction of the ‘monitorial system’ that gave some impetus to the idea of preparing people for the job of teaching.

The Monitorial System

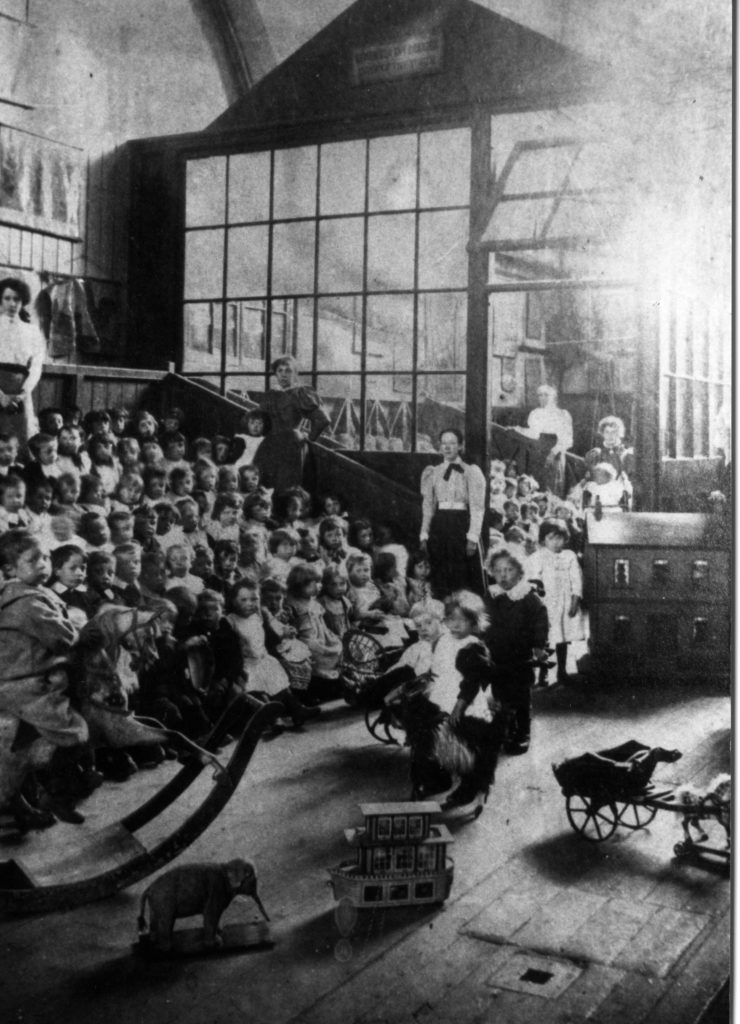

When the Pembrey Copperworks School was opened in 1855 the staffing included three paid monitors in the girls’ school and one in the boy’s school. They were at that time paid by the managers of the school. The monitorial system was developed by Joseph Lancaster in London and Andrew Bell in Madras. Lancaster, an English Quaker, established a “training ” institution in connection with his free boarding school for poor children at the Borough Road in London. Unable to pay for additional teachers he used selected ‘monitors’ from the school to teach younger children who were, in large numbers, sitting in a hall in rows, and often in a gallery. The schoolmaster would teach the monitors who would relay the lesson to the row. It was formal and almost militaristic with an emphasis on rote learning and memorization. Image gallery

The training at Borough Road was around three months and comprised of learning the system of which the school was regarded as a model. It was not so much education as learning the formula and tricks of the system, and the system was essentially about economy and efficiency. The regime was strict and arduous. Rising at 5.00am, the boys would spend an hour before 7.00am in private study after which they assembled in a Bible class and were questioned in their knowledge of the Scriptures. They worked as monitors in the school for three hours in the morning and three also in the afternoon. For another two hours they received instruction in subjects and the rest of the evening was spent in preparing exercises for the following day.

There were also similar schools set up by the Anglican Church and inspired by Andrew Bell, a Scottish Episcopalian priest. The competition with Lancaster’s non-denominational approach was the catalyst for the establishment of ‘The National Society for Promoting the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church’, known as the National Society. The British and Foreign Schools Society and the National Society remained in a state of opposition and tension for many years.

Pupil Teachers

In the early years of the Pembrey Copperworks School two pupil teachers were employed in the girls’ school and two in the boys’ school, all financed by the Government. The pupil-teacher system arose from the work of David Stow (1793-1864) and James Kay-Shuttleworth (1804-1877), the former a Free Church Scottish pioneer in teacher training and the latter a politician and educationist. Until their influence there was little change in teacher training despite the fact that the monitorial system was recognised as deficient in that did not educate the ‘teachers’ and was largely mechanistic. Neither were there secondary schools to provide a basis for training at a mature age.

Stow’s method involved ‘the interaction of the cultivated with the less cultivated mind’ and was based on training knowledgeable teachers who were both instructed in school subjects and were taught teaching skills. There were still examples of masters and mistresses who were unable to write and in some cases unable to read. His Glasgow ‘normal training seminary’ and school, opened in 1836, was effectively the first teacher-training college in Great Britain and his trained teachers were sent out to schools throughout the country and beyond.

Kay-Shuttleworth, as one of the Assistant Poor Law Commissioners and secretary of the Committee of Council for Education between 1839 and 1849, believed that the way to improve education of the working class was to improve the training of teachers and attract those of a good character. Influenced by David Stow’s approach and impressed by the seminaries in Switzerland, he developed the idea of apprenticing selected monitors as ‘pupil teachers’ for a period of five years. They needed to be called to a simple life of educating poor children and would be trained in character and knowledge. His training college for teachers at Battersea, opened in 1839-40, was the first in England.

In 1846 Kay-Shuttleworth launched a national scheme of pupil-teachers in which, under Government inspection, the brightest scholars would be apprenticed for five years (from 13-18 years of age) to the head master or mistress providing that the teacher was competent to conduct the apprenticeship. The pupil-teachers (along with any stipendiary monitors) would be examined each year and be paid from £10 to £20 and from £5 to £12 10s. respectively according to the length of service and gender. The master or mistress would be paid for their training and supervision – £5 for one, or £9 for two, or £12 for three pupil teachers and £3 per annum more for each additional apprentice. When the apprenticeship was completed pupil teachers could enter a competitive examination (the ‘Queens’s Scholarship’) which would admit the pupil-teacher to a place in a training college with a grant of £25 for men and £20 for women.

As a result of the pressure placed upon the head teacher to supervise the pupil-teacher there was a movement towards Pupil Teachers’ Centres which came into operation in 1881. The hours of pupil teachers were reduced and they might attend classes at a centre for part of the day.

The life of the pupil-teacher was challenging. In the earlier times the day would involve 1½ hours instruction from the master or mistress, 5 hours teaching, one hour looking after books and apparatus and also evening private study. It was a cheap way of providing staff although restrictions were later placed upon the number of children (40) for each pupil-teacher. By 1860 the training college system was flourishing and 34 colleges were providing training for 2,388 students. This was to a large extent the result of the pupil-teacher system which was turning out better teachers but the standard of teaching was still poor and they were criticised for being too mechanical and pedantic and dry and bookish in their approaches. However, the system was successful in bridging the gap between the elementary school and the training institution, and ironically delayed the introduction of what was really needed – a proper secondary educational provision.

One of the pupil-teachers at the Copperworks School was Mathilde Bowser who graduated through the monitor’s role to pupil-teacher and later became the head teacher of the infants’ school. There is an article on the website about her life.

Despite the growth in training colleges by 1900 only 30% of elementary teachers were trained and certified. It seems around 25% were certified but untrained and 45% were former pupil-teachers who were neither trained at colleges nor certified in any other way. By 1902 three quarters of the teachers in the Voluntary and Board Schools were still untrained.

Sources

- The Training of Teachers in England and Wales during the 19th Century. R.W.Rich, CUP, 1933.

- History of Elementary Education in England and Wales from 1800 to the Present Day, C. Birchenough, W.B. Clive, 1914.

- Life in a Victorian School, Pamela Horn, Pitkin, 2013.

- The Victorian Schoolroom, Trevor May, Shire Publications, 1994.

GRAHAM DAVIES June 2021