WOMEN AS TEACHERS

“The hand that rocks the cradle rules the world”, so says the old adage. But it gives a somewhat false impression of the status of women – their sphere was very much the hearth and home. When in 1870 all children were to be given the opportunity of a school education the girls’ curriculum was very much directed towards subjects that would help them be “good wives” and home managers.

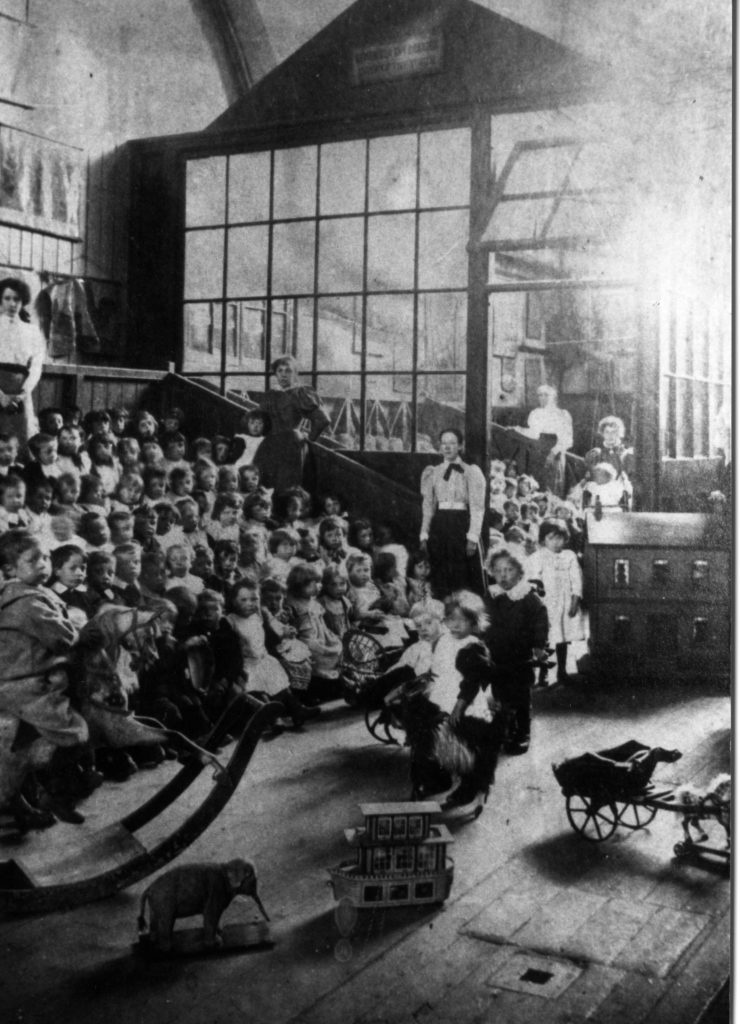

In the 19th century there were not many jobs open to women outside the home, but teaching was to become one of them. There had always been governesses for the rich, ragged schools and dame schools for the poor as well as the Sunday Schools as the great educators of what were regarded as the ‘lower orders’. Yet as the school movement grew it became apparent that teachers with some kind of training were needed, and the pupil teacher, following the demise of the monitorial system, was seen as a way to address this. (See especially the article ‘Teachers in the 19th Century’)

Mathilda Bowser from Pembrey Copperworks School became a pupil-teacher in 1889. Boys and girls became pupil-teachers usually around the age of 13 to 15 years, but many boys later left the training to pursue more lucrative jobs. Although pay was not high, women were attracted to teaching because it promised reasonable pay and better prospects than factory work or domestic service. It also provided independence for unmarried women, even though they were paid less than men. For example a male pupil-teacher was on average paid £13.9d per year while a female was paid £12.15s.

A typical profile of a girl pupil-teacher was given by a witness to the Newcastle Commission in 1861. The girl would come from a large working class family, perhaps the only older girl, and she would have to do her share of household tasks, both for the good of the family and also for her own good. For if she failed to get a Queen’s Scholarship, or if she did marry she would not be a good housewife not having had experience of domestic life. Parents might be suspicious that a certified schoolmistress “will not be the person to whom sensible and thoughtful parents of humble life will care to intrust with the formation of the character of their girls”.

At the end of their pupil teacher apprenticeship the pupil teachers could take the Queen’s scholarship exam and, if they passed, could go on to a training college for which grants were given or they could remain in the classroom as unqualified teachers and continue to take exams and be annually tested by the School Inspector.

Mathilde Bowser, our Copperworks headteacher, never married. Women teachers, when they married were expected to resign. This was the case until after the second world war when the marriage bars for women in teaching and the civil service began to be dissolved.

Women were also held to a high moral code. They were expected to conform to and to demonstrate the values and attitudes of the Christian faith, often to a greater extent than their male colleagues. Also, a certain dress code was expected and some education committees forbade the wearing of “flowers, ornaments or finery”, since they were afraid it might distract their pupils. A sober style of dress was required.

Victorian society was dominated by social class, and this proved to be the case for teachers as well. Dorothea Beale, one of the promotors of higher education for women, stated in 1866 that her school admitted only the daughters of independent or professional men. Whilst at the other end of the spectrum Elizabeth Andrews records how she had a great desire to be a teacher and how, as an unpaid helper in the classroom supported by her headmistress, she was unable to start as a pupil-teacher. The family couldn’t afford the extra train fare to Aberdare College even though she would have been paid as a pupil teacher. More importantly she was needed to help out at home and her career was very much secondary.

It was thought that working class parents would not want their daughters to be taught by middle class teachers who would give them ideas above their station, so it was not seen as important for women to train to a higher level and for them to go to training college or university They would continue in the classroom learning “on the job”, being paid less and an attractive employment opportunity for Education Boards.

To become a pupil-teacher a certain level of education was required. As well as good standards in reading, grammar, arithmetic and geography, girls also were expected be able to sew neatly and to knit. When training as a pupil-teacher expectations were not as high for girls as it was for boys, and the curriculum presented to them not so rigorous. For example, algebra, surveying, use of the globes and geography of the British Empire was substituted by special proficiency in sewing.

The scale of payments to schoolmistresses was two-thirds of that of men, which diminished their status even though gradually women proved themselves academically to be the equal of men in education. ‘Domestic economy’ was always an extra for women for the ties of women to hearth and home proved difficult to break.

There is no doubt that the mass education of the poor eventually allowed women a way in to a professional career in education but, as in all areas of life, it was a long hard struggle to gain some kind of equality with men.

Sources

- The Training of Teachers in England And Wales During The Nineteenth Century, R.W.Rich, Cambridge University Press, 1933.

- History Of Elementary Education in England and Wales, Charles Birchenough, University Tutorial Press, 1930.

- A Woman’s Work Is Never Done, Elizabeth Andrews, Honno Classics, 2006.

- Life In A Victorian School, Pamela Horn, Pitkin Guides.

ELLEN DAVIES July 2021