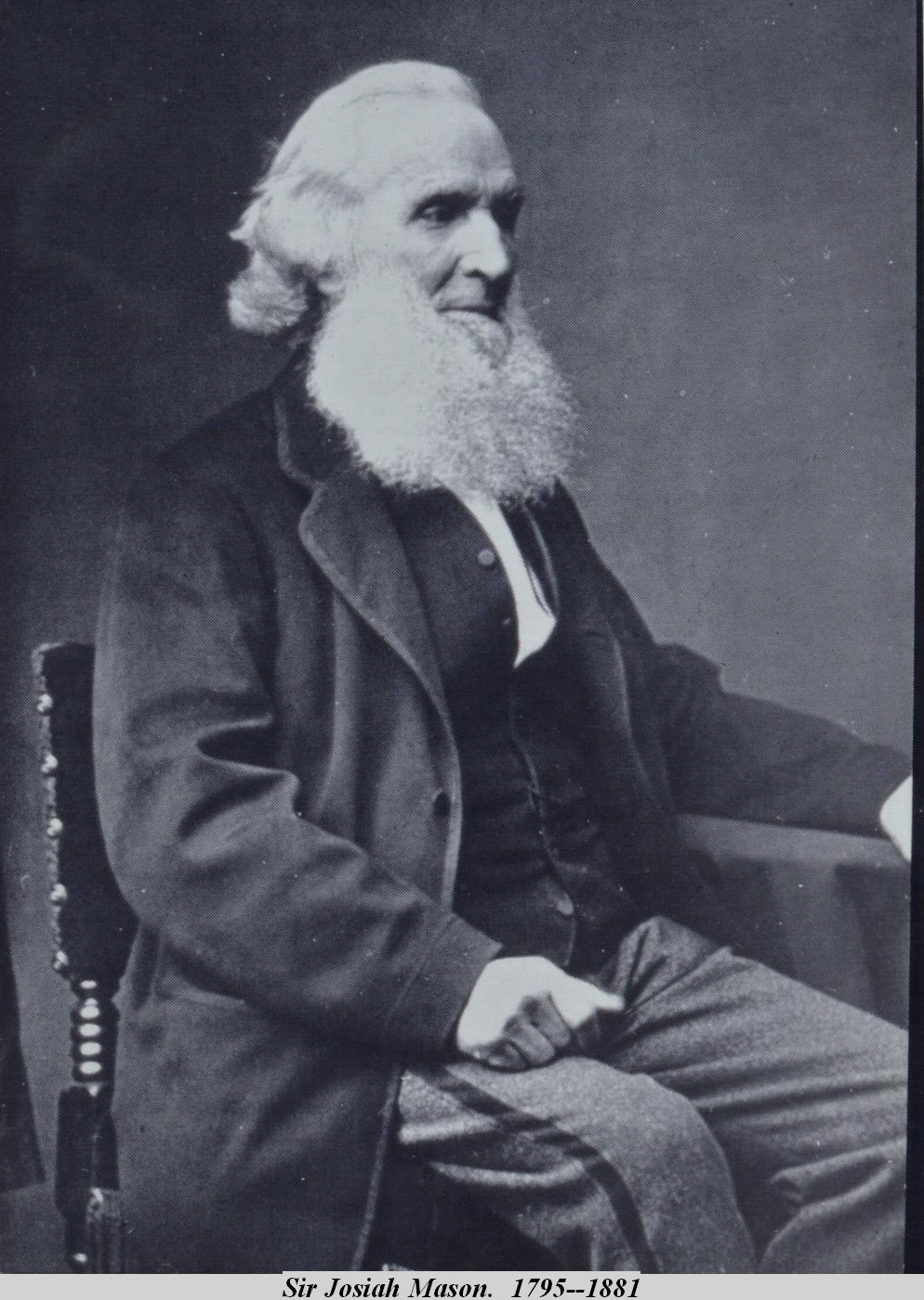

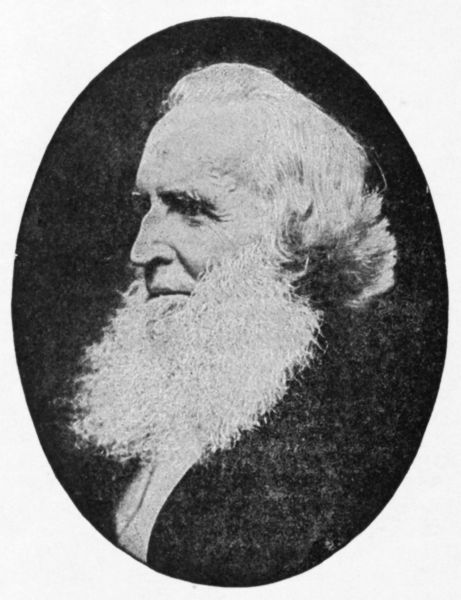

SIR JOSIAH MASON

The early days

Courtesy Josiah Mason Trust

Much is made of the philanthropy of George Elkington and his sons in their influence and activity in Pembrey and Burry Port, and this is justifiable. However, I find Sir Josiah Mason the more remarkable character and the more widely recognised as a philanthropist.

He was very much a self-made man. He had no formal training, had no trade and served no apprenticeship. Yet there was an innate desire to do something in the world and to achieve something. From the age of eight years he began to work in some sort of business. At first it was selling cakes in the streets to a regular clientele. At one time he collected copper money and wrapped them up in five shilling packets, and was remunerated by the fee of one penny for every pound. His last street trading was in fruit and vegetables which he sold door-to-door.

His next venture was shoemaking in which he excelled, and during this time he taught himself to write and even obtained some casual work as a letter writer for poor people. He read a wide range of books and in his studies was helped by lessons at the Unitarian Sunday school.

It was the move from Kidderminster to Birmingham that opened up for him the most promising employment, the first with his uncle at his glass works and then as a manager of a business making split rings. This business he bought and developed, introducing the lucrative steel pen trade. He was now only 28 years old and, as a result of his ingenuity and passion for improvement, soon became the largest pen maker in the world, employing almost 1000 people. Most of his pens were made under the name of Perry and Co.

Here is a photo of some nibs which I own, made in Mason’s factory. Both Mason’s and Perry’s names are on the nibs.

Elkington and Mason

Courtesy Josiah Mason Trust

In the 1840s George and Henry Elkington, in their Birmingham factory, were working on applying the electroplating process in a commercial way. After the research of John Wright which stabilised the process, the Elkingtons needed finance and organisation to ensure progress and development of the industry. In 1842 Josiah Mason entered into partnership with them, against the advice of many, and provided not only capital but also the required business experience and vigour. The Elkington Archive (Birmingham Library) suggests that George Elkington put £55,000 pounds into the business, Mason put £35,000 and the profits were one third to Mason and two thirds to Elkington. The partnership, dating from 1842, lasted until 1865 and was dissolved just before the death of George Elkington. On a number of occasions he had been invited by Herr Alfred Krupp, the director of the famous steel works at Essen, to become part of his establishment. However Mason declined, preferring to stay in employment in Birmingham.

The Copper Works

The firm’s ingenious chemist, Alexander Parkes, developed a process for smelting copper ore and purifying the copper by means of phosphorous. Elkington and Mason acquired the patent and they needed a copper works for the smelting at a place which was convenient to receive the copper ore, mainly at first from Cornwall. Parkes had suggested a site near Llanelly and Elkington and Mason, after visiting South Wales, favoured an area 3 miles away where there was already a dock available. Although Swansea was the centre of copper smelting at the time, Mason was keen to move along the coast from the pollution and build where the air was fresher. What later became Burry Port was described by one early publication in 1882 as “nothing to be seen but the neglected dock, one public house and an extensive tract of sand – a rabbit warren”.(1)

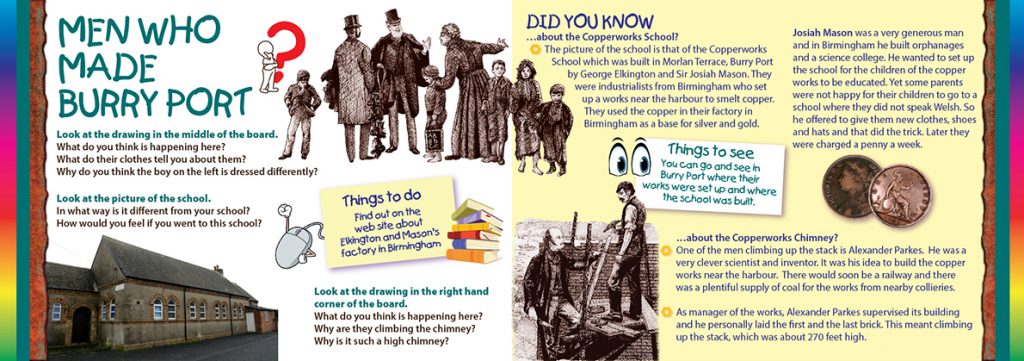

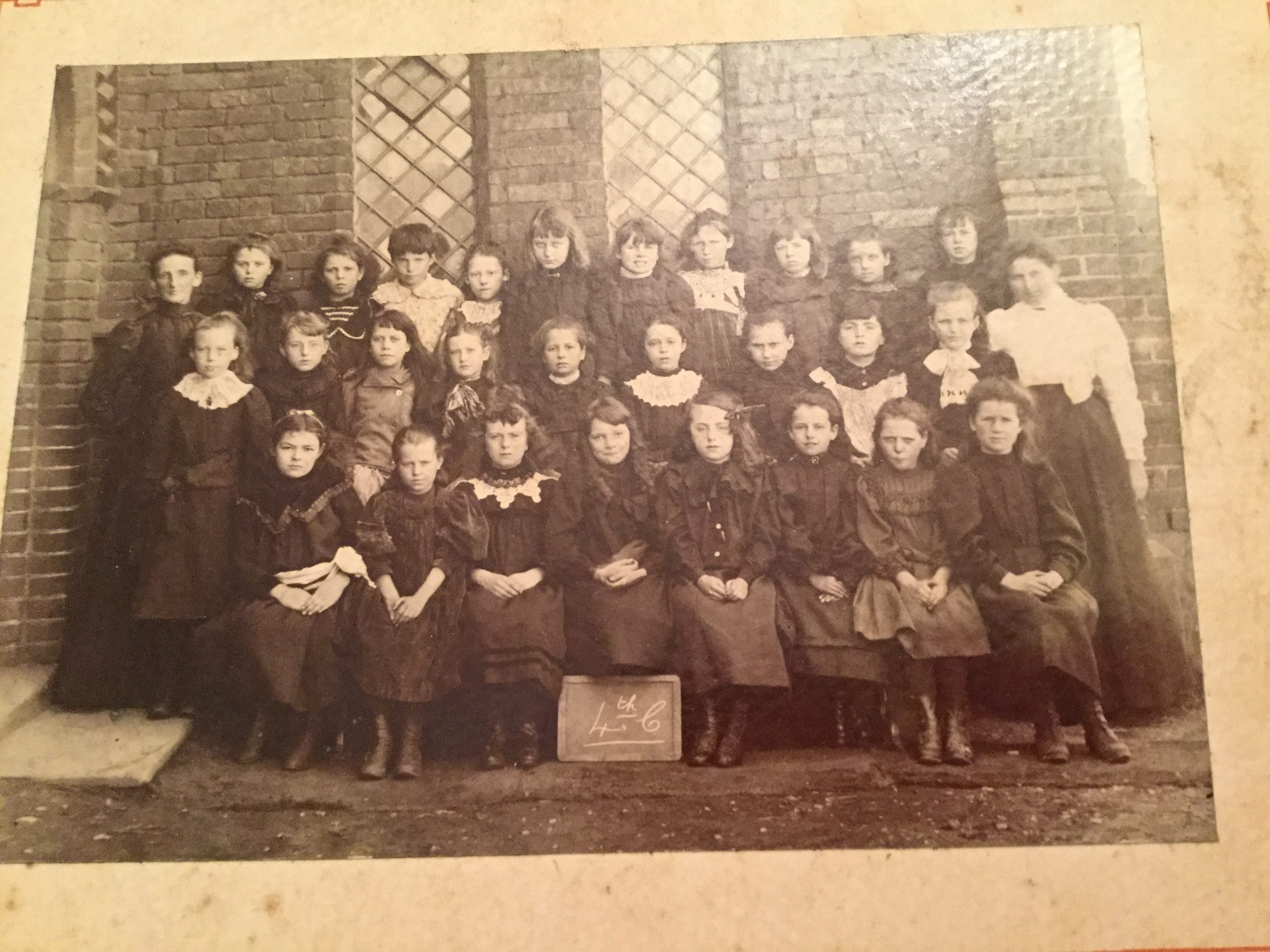

The Copperworks School

Courtesy Ray Hobbs

While he was involved with the Copper Works (although, like Elkington, he never lived in Burry Port) Josiah Mason furthered his interest in the education of children. Using bricks from the brickworks the company had built, he constructed the Copperworks School at a cost of £1,700, mainly for the children of the workers. Initially it comprised separate boys, girls and Infant sections with about 500 pupils. It was a non-denominational school, whereas others in the area were church schools. It had a good reputation with qualified staff, but the local copper-smelters and colliers were reluctant to send their children to learn English. Mason solved this by bringing down from Birmingham a supply of hats, bonnets, shoes and other clothing which he gave out as a reward fo

Courtesy Moira Thomas

r attending. The school was soon full and later parents were willing to pay a penny each week. One early writer in 1882 wrote: “..the moral and intellectual interests of the people were cared for as well as their material prosperity; and habits of order and good conduct were established among a class proverbially rude and uncultivated” (2) Not a hugely complimentary comment about the good people of Burry Port in 1855!

Josiah Mason – Philanthropist

Courtesy J. M. Trust

Mason’s great business acumen along with his energy and enthusiasm brought him great wealth. Yet he was not a selfish man and he regarded himself as a steward of this wealth and wanted to use it particularly for women and children in need. Consequently his first venture was an almhouse for spinsters and widows over 50 years of age and orphaned girls which opened in Erdington, a suburb of Birmingham, in 1858. His second venture in 1869 was an orphanage for 26 women and 300 children on a 13 acre site with playgrounds and gardens. His third great project was the establishment of a science college which challenged the traditional non-vocational university tradition and aimed at providing a more practical scientific education for all which linked with the artistic, manufacturing and industrial pursuits of the area.

Courtesy J.M. Trust

References

- Josiah Mason: A Biography, John Thackray Bunce, General Books, Memphis, 1882.

- Josiah Mason: A Biography, John Thackray Bunce, General Books, Memphis, 1882

Other sources

- Josiah Mason 1795-1881, Brian Jones, Brewin Books, Studley, 1985. 2.

- A Historical Miscellany, Bk. 2, John A Nicholson, Llanelli Borough Council, 1984.

GRAHAM DAVIES

A VISIT TO THE ELKINGTON AND MASON ELECTROPLATING WORKS

in Newhall Street

Photo – Graham Davies

The premises of H & GR Elkington, later to become Elkington, Mason & Co, lie in Newhall Street, Birmingham. What remained after the closure of the factory became the home of the Museum of Science and now the rest of the buildings are surrounded by modern developments. The front of the building is shown below along with the plaque in honour of George Elkington.

It was to this factory that copper ingots were brought from the Copperworks in Burry Port. The Birmingham and Fazeley Canal actually flowed through the works and the now demolished workshops and warehouses

Photo – Graham Davies

have been replaced by a commercial and residential development. The photo below is taken from a position inside the old factory.

It was the Italian chemist, Luigi Brugnatelli, who invented electroplating in 1805. George Elkington realised the opportunities afforded by this technique which was in its early stages, and took out a number of patents including the process of the Birmingham surgeon John Wright. Wright had discovered that potassium cyanide was a suitable electrolyte for gold and silver electroplating and produced a stable and even coating. Following the partnership with Josiah Mason, the Elkington works and business grew dramatically with 1000 employees on this one site. Their products became world famous and British and foreign dignitaries visited the works. Queen Victoria’s husband Prince Albert was presented with a delicate spider’s web that had been electroplated using a method devised by Parkes. The company supplied cutlery for the luxury dining sections on board the Titanic and other ships in the White Star Line fleet. Probably the most well-known example of Elkington plate is the Wimbledon Ladies Singles Trophy. It is possible to view many other examples of Elkington Silver in the Birmingham City Museum.

Josiah Mason believed that the firm needed to diversify and move away from the more expensive items and move towards the everyday things that ordinary people could afford – for example jewellery and cutlery. Consequently Elkington silver transformed the Jewellery Quarter in Birmingham.

Below is a photo of a sauce ladle from around 1888 which has the E and Co stamped on the reverse of the handle and a crown inside a shield. The “crown” was deleted from the Elkington in 1898.

Sources

Sources

- Explore the Birmingham Jewellery Quarter, Birmingham City Guide.

- S. Leader, History of Elkington & Co. 1913 (Typescript, Birmingham Archives.)

- All photos – Graham Davies

GRAHAM DAVIES

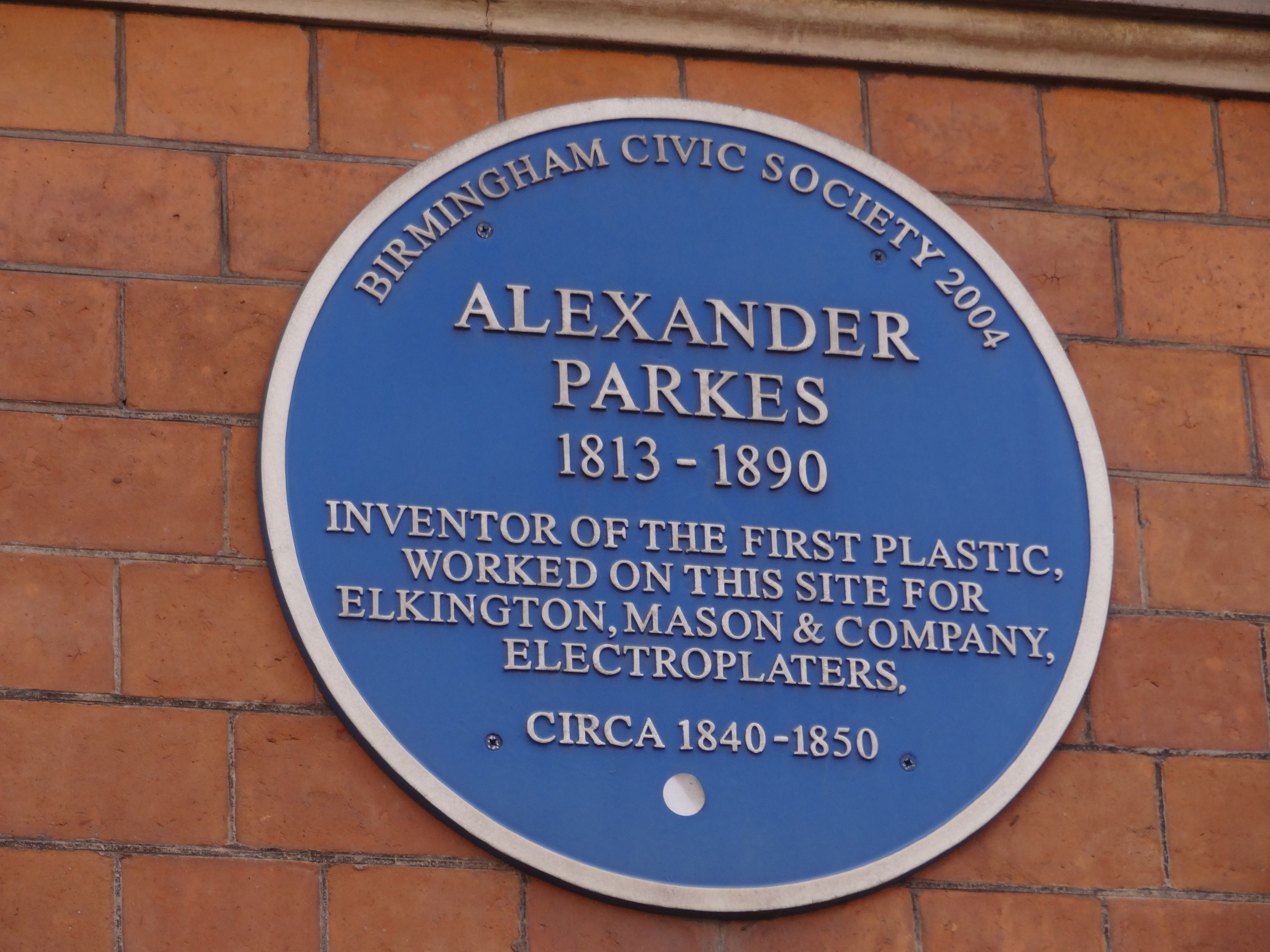

MORE ABOUT ALEXANDER PARKES (1813 – 1890)

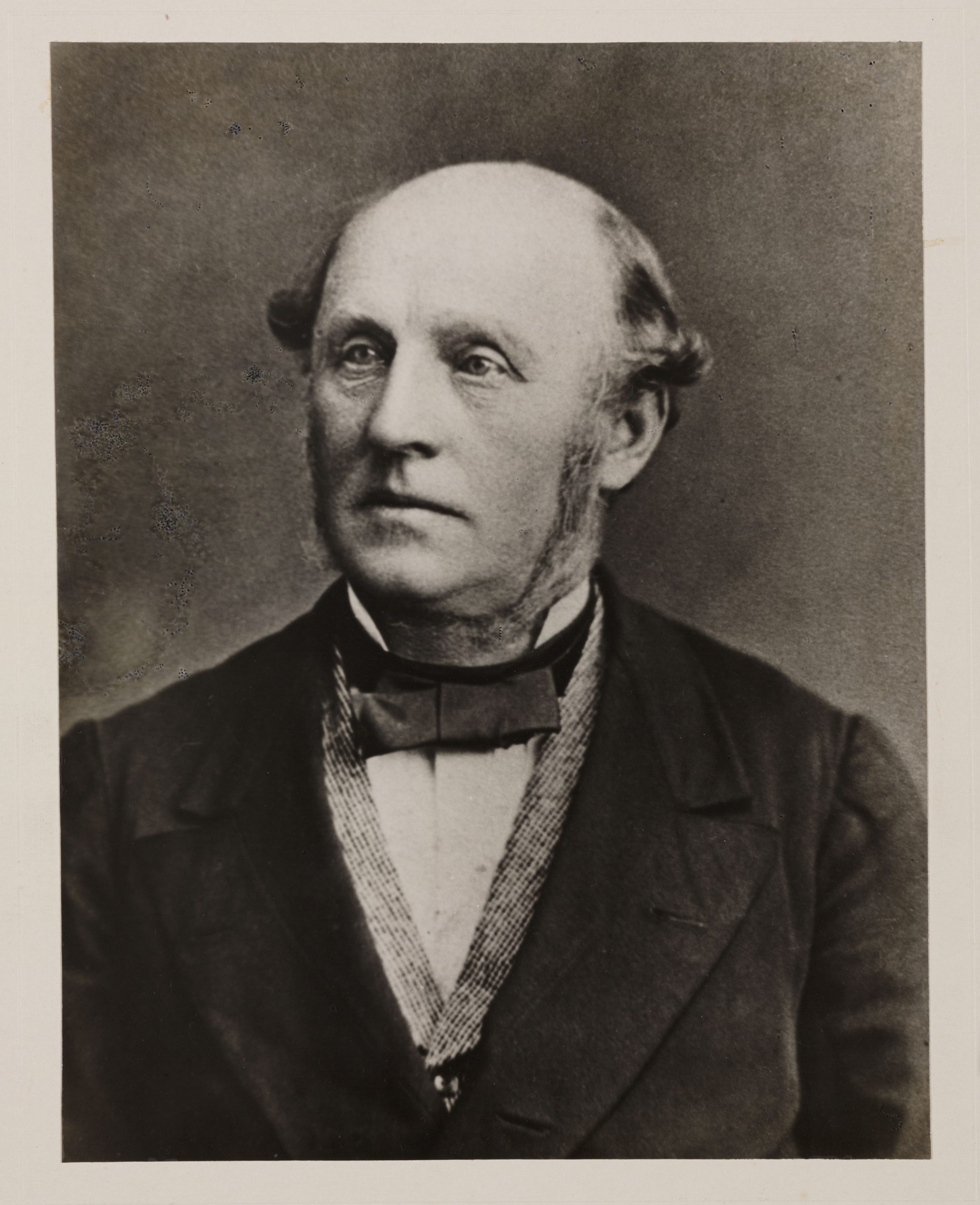

Alexander Parkes was a chemist and prolific inventor, primarily remembered as the inventor of the first synthetic plastic. Parkes took out at least around 66 patents during his career, most of them relating to electroplating processes.

A great nephew of Josiah Mason, Alexander Parkes was the son of a brass lock manufacturer. He was born in Suffolk Street, Birmingham in 1813. As a child he delighted in making things and was especially good at kite making and geometric stars. He spent a long time with his father lock-making, and on one occasion a complicated lock was brought in to see if Mr Parkes could copy it. Looking at the construction he declined, but Alexander, who was standing nearby, whispered that he could. He explained the workings and a lucrative order was placed with his father.

A great nephew of Josiah Mason, Alexander Parkes was the son of a brass lock manufacturer. He was born in Suffolk Street, Birmingham in 1813. As a child he delighted in making things and was especially good at kite making and geometric stars. He spent a long time with his father lock-making, and on one occasion a complicated lock was brought in to see if Mr Parkes could copy it. Looking at the construction he declined, but Alexander, who was standing nearby, whispered that he could. He explained the workings and a lucrative order was placed with his father.

He married Jane Henshall Moore in Birmingham in 1837, and in the 1841 Census he was recorded as an “artist”, living in Ladywood, Birmingham, with John Parkes (3), Jane Parkes (20) and Catherine Parkes (1). He was apprenticed to Messenger & Sons, a brass founders, and later went to work at the Elkington and Mason factory in Newhall Street, Birmingham, where he was in charge of the casting department. There he became interested in electro-plating, a subject that was to interest him throughout his life.

His first patent was in 1841 for the electro-deposition of works of art. Parkes had trained as a decorative metal worker and showed extraordinary skill electro-plating flowers and other fragile objects including a spider’s web presented to Prince Albert on a visit to the Works. In early patents he styled himself as an artist before a chemist. He was a very creative man. The story is told how he once, when studying drawing, made a life size drawing of Ruben’s ‘Descent from the Cross’ on the blank wall of a nearby house. But owing to pressure of work he didn’t complete it: the drawing was the wonder of the neighbourhood for many years.

Another early patent (probably 1846) followed the discovery of the cold vulcanization process, a method of waterproofing fabrics by means of a solution of rubber and carbon disulfide. This was carried out by Elkington, Mason and Co for a number of years and later sold to Macintosh & Co. The rest is history!!

Those who knew him say he was a respected and friendly man. Neighbours would come to his house for help in fixing things. He was constantly trying out new things and he would wake his wife in the night to jot down an idea that had just come to him. It was said of him that unfortunately he could never really be successful in business as he had too many irons in the fire and his mind was never still, always thinking of the next idea.

Parkes moved to South Wales in 1849 after the death of his wife, Jane Henshall Parkes. In the 1851 Census, he is recorded as a “copper smelter”, living in Pembrey with his son Henry James Parkes (6), brother Henry Parkes (26 and a chemist) and sister Ellen Catherine Parkes (21). He left South Wales in 1853. Parkes came to South Wales on the behalf of Elkington & Mason to choose a site for a copper smelting works to supply their factory in Birmingham. He chose Burry Port for the transport links, availability of materials and also, showing the humanity of the man, for the healthy situation by the sea. His role in Pembrey was to supervise the erection of Elkington, Mason and Co’s Copper (smelting) Works, based on his patent, which he had sold to the Elkingtons. As manager of the Works, he supervised its building and personally laid the first and last bricks, climbing up the 82m (270 feet) stack.

During this time, Parkes made one of his most significant inventions, which was a method of extracting silver from lead ore. This procedure, commonly called the Parkes process, involves adding zinc to lead and melting the two together. When stirred, the molten zinc reacts and forms compounds with any silver and gold present in the lead. These zinc compounds are lighter than the lead and, on cooling, form a crust that can be readily removed. This was used at Nevill, Sims, Druce and Co. Works at Llanelly.

Courtesy Science Museum Pictorial

An early biography describes two other fascinating discoveries while he was in South Wales. During the time of the Crimean War, in 1855 he had invented a new, more powerful powder than ordinary gunpowder suitable for small arms, cannons, shells, or blasting purposes. At his own expense he held a public trial on of the seashore at Burry Port on 17th August 1855 in shells of 13 inches and 21 inches diameter. The effects of the explosions were terrific – some of the pieces being carried nearly a mile from the spot, and was reported in the Times and other papers of that date. The government was offered the invention, but insisted that Parkes divulged the secret of the composition of the powder. This he did not agree to and friends advised him to offer it to the Russian or French governments, but his patriotic feelings would not permit him to do.

Another of his discoveries while in Burry Port was the manufacture of fire bricks from sea sand by compression or from the ground siliceous boulders locally called ‘popples’ found on Kidwelly Mountain.

Finding that additional markets were wanted for the use of anthracite, he discovered a method of burning it under the boilers of steam engines in smelting and other furnaces by introducing jets of steam under or through the fire bars made hollow for the purpose but he did not have an opportunity of getting the method adopted and never derived any benefit, although later the method was extensively used.

After leaving South Wales, he is recorded as marrying Mary Ann Roderick in Gloucester in 1854.

Around 1855 Parkes’s most memorable invention was made, when he produced a flexible, durable material called Parkesine, from a mixture of chloroform and castor oil. It was described as “a substance hard as horn, but as flexible as leather, capable of being cast or stamped, painted, dyed or carved.” This led to the development of the first plastic, celluloid. Parkesine was displayed at the 1862 Great International Exhibition in London and the 1867 Exhibition in Paris, receiving medals on both occasions.

According to the 1861 Census, he was then a “tube manufacturer, living in St Thomas, Birmingham, with ten others of the Parkes family. In 1865, Alexander Parkes was manager of Stephenson Metal Tube and Copper Roller Co, Liverpool Street, Birmingham. In 1871, he was still living with 10 others of the Parkes family, with a title of “chemist”, and living in Erdington, Birmingham.

In 1866 he established the Parkesine Company in London, regarded as laying the foundations of the plastics industry. Unfortunately it closed in 1868. The patent was further developed by J.W.Hyatt and Baekeland in USA. In 1881 he left Birmingham and moved to London. He died in West Dulwich, near London, on June 29th 1890.

Sources of Information:

1. Graces Guide to British Industrial History (quoting Birmingham, England, Marriages and Banns, 1754-1937;

2. 1841 Census; Birmingham, England, Burials, 1813-1964;

3. 1851 Census; Gloucestershire, England, Marriages and Banns, 1754-1938;

4. 1861 Census;

5. 1865 Institution of Mechanical Engineers;

6. 1871 Census;

7. Encyclopaedia Britannica Online;

8. History of Plastics; Dictionary of National Biography, Volumes 1-20, 22 for Alexander Parkes).

9. Science & Society Picture Library

10. A Short Memoir of Alexander Parkes: 1813-1890 Chemist and Inventor,Printed for Private Circulation.

RICHARD EDMUNDS and ELLEN DAVIES June and November 2019