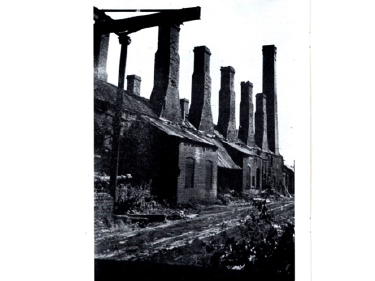

The site of the former Ashburnham Tinplate Works – now Parsons Pickles factory.

THE PROCESS OF TINPLATING

Tinplate production involves the rolling and preparation of steel sheets prior to coating with tin which prevents rusting. The Ashburnham Works (1890 – 1953) employed the pack mill process of production whereby a long flat strip of steel was manufactured into packs of individual tinplates.

When the works closed in 1953 this method of production had been superseded by strip mills; from America, which could produce tinplate in larger quantities and more economically.

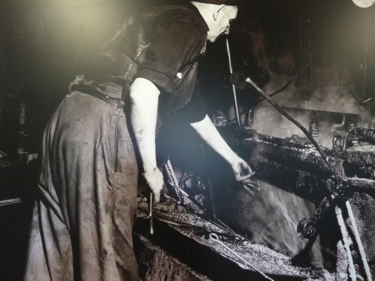

Conditions in tinplate works seem very harsh by today’s standards. “The heat was infernal, the fumes insufferable, the noise stupefying. Screaming-hot jagged edged plates, arcing through the air on long tongs or skidding along the iron-surfaced floor, caused burns and crippling lacerations.” This is how Alun John Richards described the hot end of the works where the mill team worked. The cold end he says was “just as busy, but with less heat and less strife”. (1) It was here that the sheets were pickled, annealed, cold rolled, washed, cleaned and sorted and the work was regarded as being generally lighter.

It all begins with a strip of steel known as a tin bar which measures about sixteen feet long. The bars come from local steel works and on arrival are sheared or cut by a bar cutter into short lengths depending on the finished size of the sheet to be made.

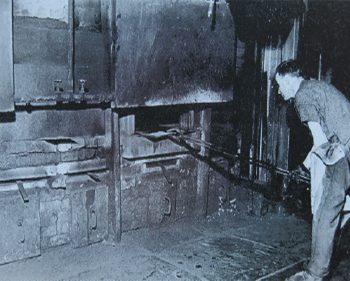

The bars then go to be heated in a furnace where the furnace man heats thirty to forty bars at a time to blood heat. The furnace man is the second man of the team with the responsibility for adjusting the gap between the rolls.

It is now the job of the rollerman to pass the hot bars through hot rolls to the behinder who in turn passes it back over the rolls to the rollerman man who, in the meantime, has put another bar through the rolls. This happens four or five times until the bars are rolled into sheets. Between each rolling the spaces between the rolls is decreased by means of screw pins.

The rollerman is the leader of the team and he is responsible for the overall quality of the sheets and the speed of work.

The sheet now goes back to the furnace to be reheated and rolled until it is twice its original length. The doubler with the aid of tongs and his special boot folds and compresses the sheet and lifts it onto a table where the shearer trims it. This is repeated until there are eight thin pieces of steel from the original tin bar.

The behinder now piles the sheets to cool, ready to be sheared to the exact size by power driven shears.

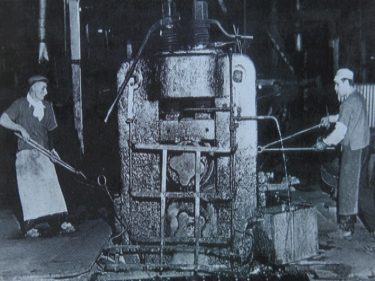

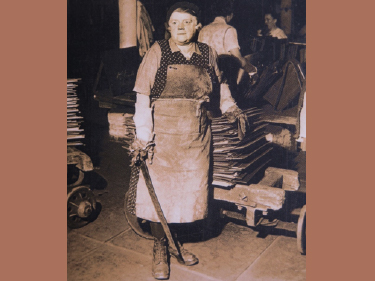

After rolling, shearing and stacking the sheets now need to be separated. This job is done by women openers. For protection they wear a leather and lead pad in the palm of their hand and use a cleaver to separate stubborn sheets.

Rolling and heating the steel has caused a scale to form on the surface. To remove this they are black pickled. The sheets are loaded into racks and dipped in a bath of hot diluted sulphuric acid. The steel sheets are then rinsed in cold clean water.

Heating, rolling and doubling weakens the steel. To counteract this and to remove impurities and any moisture on the sheets they are black annealed. The process involves packing them in annealing pots, wheeling them into a furnace and heating to a high temperature for ten to fourteen hours. This is done by an annealer.

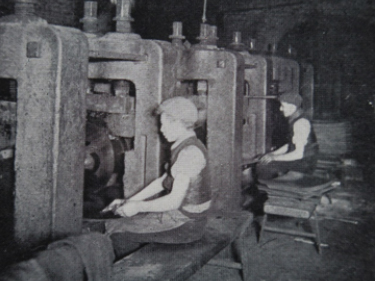

After cooling, the sheets are cold rolled to improve an uneven and porous surface. They are now fed through the roughing, intermediate and finishing rolls, a job usually done by boys as young as thirteen. Cold rolling unlike hot rolling is not meant to change the size of the sheet but to improve its quality before tinning.

Cold rolling has affected the sheets by hardening them so they are white annealed which is similar to black annealing except the furnace is cooler and the time shorter. White pickling follows to make them really clean, a process again similar to black pickling but with lower acidity and temperature. The sheets are now washed and stored in a weak acid solution until they are ready to be tinned.

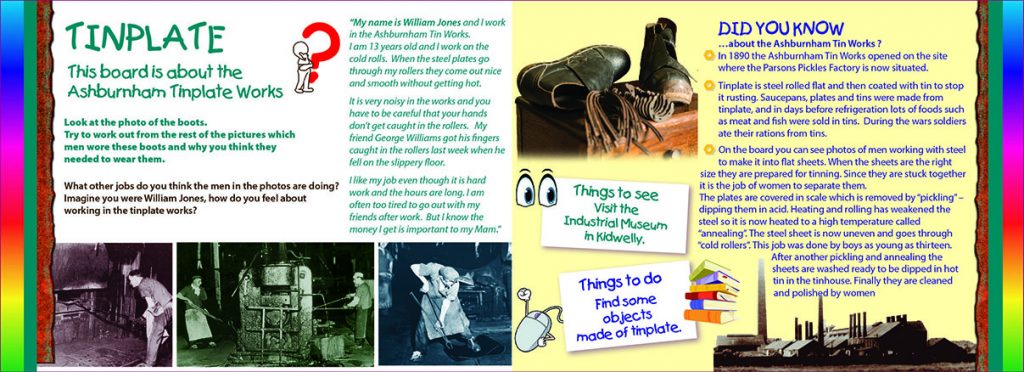

The sheets now go to the tin house where a highly skilled tinman dips each sheet into molten tin. In the tin house each tin stack has two tinning pots, a grease pot and a cleaning machine. The sheet passes through a layer of flux (zinc chloride) which cleans the sheet so that the tin will stick to it. This is done at a very high temperatures as the sheet has to be heated as well as keeping the tin hot. It then goes to a second pot where the tin is at a lower temperature and from there to a grease pot which contains palm oil which helps spread the tin evenly and removes excess tin.

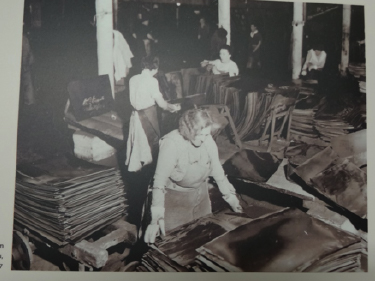

Women now clean the tinplates using a machine with cotton rolls on which bran steadily falls. This absorbs any remaining grease and a sheepskin is then used to polish the finished tinplates.

The tinplates are now sorted and packed before leaving the factory by rail.

References

- Tinplate In Wales, Alun John Richards, pages 44 and 45

Sources

- Twenty by Fourteen, A History of the Tinplate Industry 1700-1961, Paul Jenkins

- Tinplate In Wales, Alun John Richards

- Kidwelly Tinplate Works: A history, W.H. Morris

- The Industrial & Maritime History of Llanelli & Burry Port 1750 to 2000,

R.S. Craig, R. Protheroe Jones, M.V. Symons

- Tinopolis Aspects of Llanelli’s Tinplate Trade John Edwards

- Pembrey & Burry Port Further Historical Glimpses Book Three, John Nicholson

- Curator and Archive of Kidwelly Industrial Museum

- Curator and Archive of Trostre Museum, Tata Steel