PANT ACHDDU

Behind Jerusalem Chapel in Burry Port there is a derelict farmhouse known as Pant Achddu. It has its origins in Tudor times and is built in the longhouse style. The Historic Environment Record describes it as ‘a farmhouse apparently on the longhouse model, believed to be of 17th century date, with an 18th century cowhouse and 19th century outbuildings’.

One of the first references in Wales of a longhouse or ‘ty-hir’ is in a 12th century medieval poem, ‘The Dream of Rhonabwy’. When sent on a mission from Madog, Prince of Powys, he takes shelter in the longhouse of Heilyn Goch. Longhouses were found throughout Britain and Europe long before this and evidence shows they were in use in the Bronze Age period. In some cultures and parts of the world they are still lived in today.

Longhouses were single-storied, long rectangular buildings characteristic of many farmsteads in Wales during the 17th century. They were constructed using local materials. Some would use stone, others ‘clom’ which was a mixture of clay, straw and animal manure daubed over woven wicker panels attached to a timber frame and then given a protective coat of lime wash. Pant Achddu was constructed of stone rubble from the nearby mountainside. Most were thatched with bracken, reeds or straw.

Pant Achddu was built on land released by the Mansel family from the Muddlescwm Estate in 1604 and a farmhouse in the longhouse style was built on the site. Longhouses became common in Britain in the 13th century when the peasantry became more prosperous and the climate was colder and wetter. Valuable cattle had to be wintered indoors for their own good and to protect the fields. Longhouses began to disappear in arable growing parts of Britain in the middle of the 16th century whereas in Wales there were some working longhouse farms in the early twentieth century.

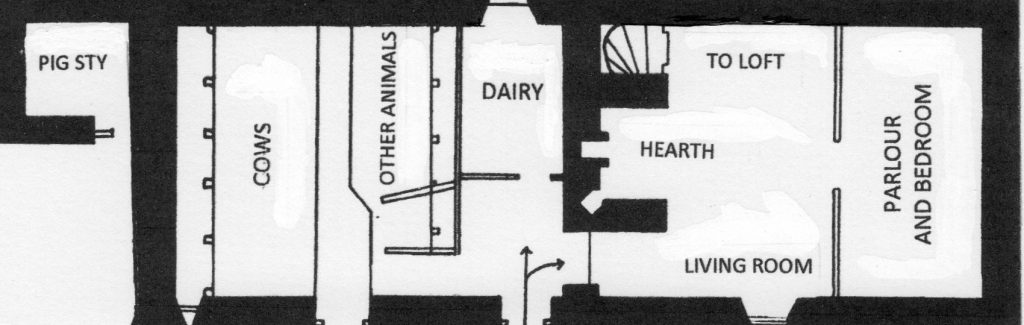

The longhouse met the needs of farmers through the centuries and, although the basic long low shape was kept, it evolved to meet the needs and comfort of its inhabitants. Some houses would have had a central hearth and chimney whereas in others the hearth and chimney would be on the end gable. Early longhouses in Wales had the entrance in the gable end of the house; most had a cross passage which separated the animals from the family quarters. In the 19th century, under the influence of Georgian architecture the design became more sophisticated and gables were added in the roof and a second storey sometimes added.

In the 17th and 18th centuries cattle rustling was common and cattle were the farmer’s most precious asset. Sold at market, both locally and in the towns and cities of England, the ancestors of Welsh black cattle always fetched a good price. The longhouse offered good protection to the farmer, his family and the animals.

The family living quarters consisted of a large room divided for living and cooking, and at the far end there would be a parlour and bedroom. The loft space would be used for storage and sleeping quarters for children and servants. Small mullioned windows covered with hessian, and later glass, gave limited light and the floor of flagstones or beaten earth would be covered with rush matting.

Mike Clement from Burry Port recalls: “As a boy I visited Pant Achddu when Sara Pantachddu was in her 90s. When you entered it felt like a portal where time had stood still for years. She sat with cushions in front of the open fire in the wall, to the right of which was a large niche in the same wall with a curtain across. This is where she slept next to the fire”.

The dairy was important for making butter and cheese which formed part of the family diet and would also be sold at the local market. Pigs kept in an adjoining pig sty was the mainstay of their winter diet. When killed and cured it would last the winter and be stored with other provisions in the loft.

For many centuries the longhouses, in all their different styles, were one of the most important types of farmhouse from the 16th century to the 19th century. Today you can visit an excellent example of a 250 year old longhouse, Cilewent, at the Welsh Folk Museum, Cardiff.

Digital IGNU Free Documentation Licence

In March 2021 Dyfed Archeological Trust stated: “We consider these buildings to be of historical interest and regional importance and it is regrettable that the site is now ruined and looks set to be demolished”.

Sources

1. Welsh Long –houses, Eurwyn William, University Of Wales Press, 1992

2. Muddlescwm Estate Papers.

3. The Dream of Rhonabwy, Y Mabinogi

ELLEN DAVIES April 2021