EARLY EDUCATION IN WALES

In the 18th century it was religion and charity that promoted most of the education in Wales. Church organisations and charitable institutions, along with a large number of private schools, were the main providers. The Sunday schools were very popular since they used the Welsh language, reflected the Welsh nonconformist beliefs and traditions, were available free of charge to all ages and did not interfere with everyday work.

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Griffith Jones’ Circulating Schools

Griffiths Jones was born in Carmarthenshire in 1683 and his idea was of a ‘circulating school’ for the rural parishes where a school building was not feasible. He suggested money should be spent on teachers who would hold classes for three months in a parish vestry or other available building and in that way reach out to large numbers of people with the least expense. The teaching was in Welsh and the focus was on reading the Bible and the catechism. His schools are regarded as instrumental in making Wales a literate nation and their fame spread throughout Europe.

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Charles

Born near St. Clear’s in 1755 Charles was a Methodist leader and popular preacher in north Wales. He continued to advance the circulating school with up to seven teachers paid for by collections made in Methodist Societies. However, he is best known for the development of the Sunday School movement, building on the work of Robert Raikes but continuing the adult classes and using the Welsh language. Despite the views of some that teaching was breaking the Sabbath by working, the movement grew rapidly with the aims of learning reading through the Bible, so that souls could be saved, and learning the catechism by rote. Charles is also remembered for his efforts to acquire and distribute bibles.

The Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge (SPCK)

The SPCK was formed in 1699 (building on the work of the Welsh Trust) by a group of friends, among whom was the industrialist Sir Humphrey Mackworth of Neath. They were concerned about the “growth of vice and immorality” and ‘ignorance of the Christian religion’ in the country and raised funds for schools for the poor across England and Wales. Their evangelical philanthropy reflected the dominant motive for the establishment of the schools – to enable people to read the Bible live morally and be useful in society. For some this was a ‘hidden curriculum’ of social conditioning to ensure that the ‘lower orders’ realised their position in society.

Joseph Lancaster

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

The established church had always regarded itself as the main provider of education and the Anglican-based school system was often resisted in nonconformist Wales. So initially the Church was hostile to the work of the Quaker Joseph Lancaster. He set up in 1801 an elementary school for poor children in London and, Influenced by the work of Andrew Bell in Madras, devised a ‘monitorial system’ using older students to teach the younger ones, who sat in rows, in a mechanical rote system. It avoided the payment of additional teachers and enabled free education of large number of children. One ‘schoolmaster’ might be responsible for up to 300 children in one large schoolroom.

The British and Foreign Schools Society

Lancaster’s initiative led in 1814 to the founding of the British and Foreign Schools Society in London. It established a number of what were called “British Schools” (as opposed to ‘National Schools’) and teacher training institutions and also provided funding for books and equipment. It was from the 1840s onwards that it began to have an impact in Wales.

National Society for Promoting the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church in England and Wales.

Known as the National Society’, it was the Anglican response to the founding of the BFSS and aimed to set up a National School in each parish in opposition to the British Schools which were non-denominational. Children would be taught the 3Rs, to read the Bible, learn the basics of the Scriptures and the Catechism and be provided with adequate books. The Society initially continued with the monitorial system until the introduction of the pupil-teacher system but also trained teachers. Despite their advantage in funding, by 1846 of the 1100 church schools in Wales only 377 were linked to the National Society.

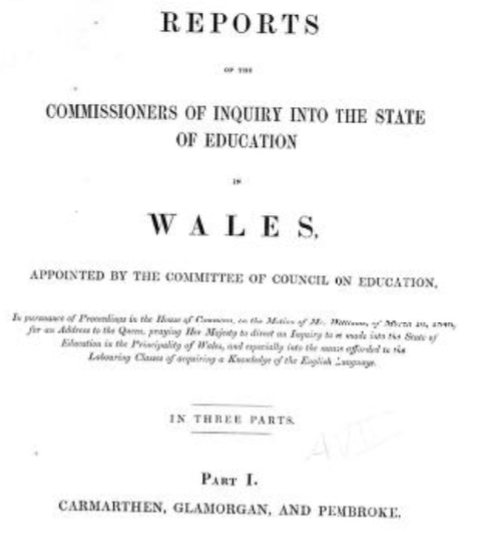

The ‘Treason of the Blue Books’

In 1847 a report into the state of education in Wales was published by the British government following an inspection of schools by a team of commissioners. The report came to be known as the ‘Treason of the Blue Books’ from the colour of its cover, and because it caused a furore especially with regard to derogatory comments made about the behaviour and morals of the Welsh people.

No doubt the rioting in Merthyr, the Rebecca Riots and the Chartist uprising in Newport presented a picture of discontent. Certainly industrialisation resulted in appalling living and working conditions, poverty and unrest. For many the cause was the lack of adequate education and the predominance of the Welsh language which was believed to be holding the back the Welsh worker. It was the ‘language of old-fashioned agriculture, of theology and of rustic life, while all the world about him is English’.

The report was scathing in its attack on the state of education in Wales; the tone was often derisory and the approach lacking in empathy. It portrayed an insufficient number of schools, inadequately trained teachers and too few children attending school and with irregular attendance. The reason for the latter was often the inability to pay the school pence and family responsibilities. The teaching of English, the medium of instruction in most schools, was poor and some teachers had no knowledge of the language. Others used English text books which the children could not read. The first teacher training college in Wales was Trinity in Carmarthen (1848 and for men only).

In truth, the educational situation was extremely poor, but no poorer than many areas in England. The commissioners in fact recognised the hunger that the Welsh had for education and praised the work of the Sunday Schools. What the grim report did was to harden attitudes toward Anglicanism, increase the support for non-conformism and galvanise the societies responsible for the provision of education in Wales. This, then, was the background to the development of works schools in Wales and the report was published in the decade before the building of the Copperworks School in Burry Port.

Sources

- A History of Education in Wales, Jones and Roderick, University of Wales Press, 2003.

- Education in Industrial Wales, Leslie Wynne Evans, 1971.

- The Blue Books of 1847, The National Library of Wales.

GRAHAM DAVIES April 2021