LIFE IN A 19TH CENTURY WORKS SCHOOL

In 1855 the great and the good of Burry Port gathered to celebrate the opening of the Copperworks Works School, built by the owners of the Copper Works, Josiah Mason and George Elkington. It followed the 19th century tradition of works schools set up primarily to educate the children of workers in the copper works, the coal mines, iron & steel works and tinplate works of the area. (See web article – ‘The Growth of Works Schools in South Wales’).

When it opened the Copperworks School was described as having “an abundance of books of every kind necessary for teaching children in reading, arithmetic, crafts and music”. The school had a good reputation and school log book entries, which had to record HMI reports, bear witness to this:

- “This school is in very good order” – 1870.

- “This school has been extremely well conducted and taught”- 1898

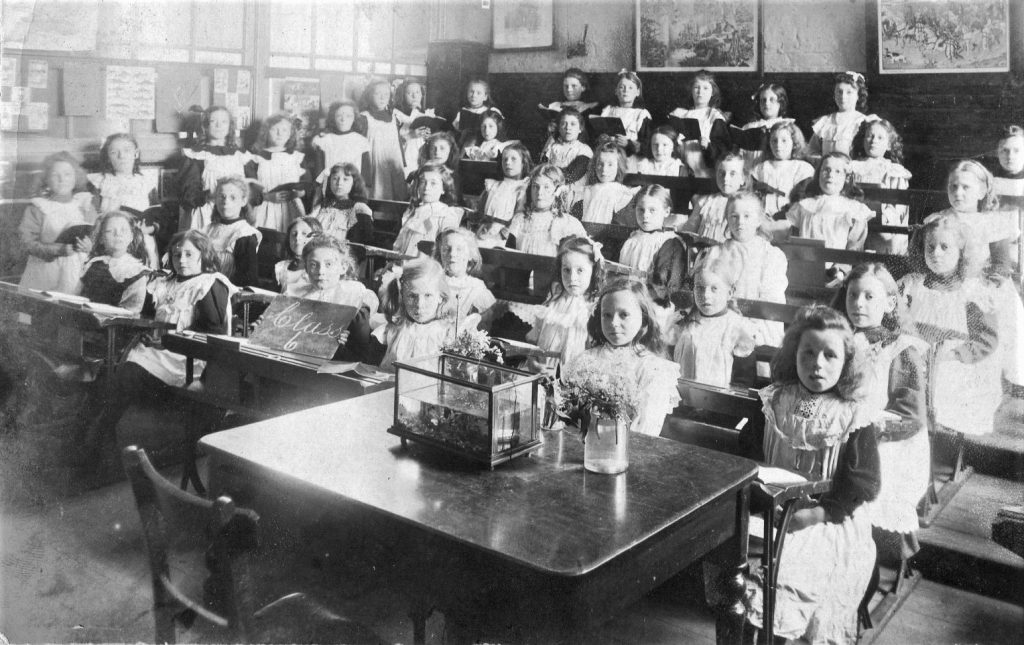

The school day began after what was to most children a long trudge to school in often cold, wet weather. At 9 o’clock the school bell signalled a military style line up and march into assembly for prayers, religious instruction and any announcements. Boys and girls were at first taught in one building but in separate schools divided by a wooden partition, with infants a part of the girls’ school.

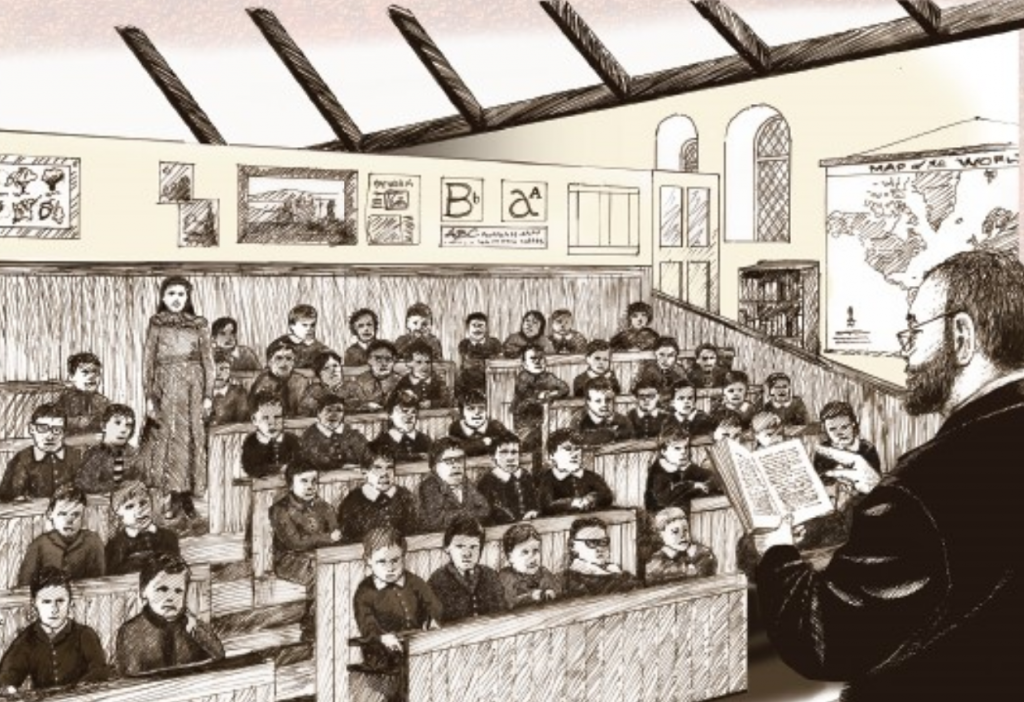

Both schools were initially divided by age into six standards, but if a child didn’t reach the appropriate level he or she would stay down and repeat the year. A feature of most school rooms of works schools was the gallery, for classes were large and the teacher needed to see all the children and all the children needed to see the teacher. These were phased out as the century progressed when individual desks and classrooms were used and when more qualified teachers were employed. The Pembrey Copperworks school was criticized in an HMI report of 1901 because “the unsuitable galleries were not yet replaced”.

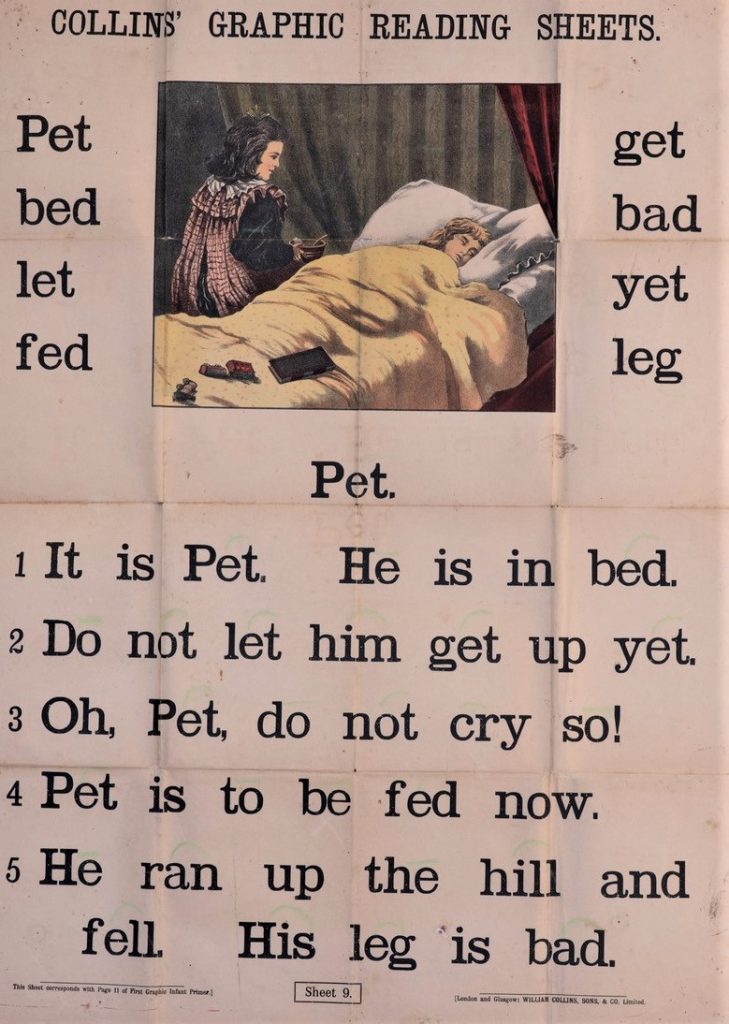

Most Victorian lessons involved listening to the teacher and copying from the blackboard. There was little or no chance to discuss ideas and to ask questions and education was a largely passive experience. Along with religious education the 3Rs were the most important part of the curriculum. At first the Bible was used to practise reading, but the concern was that they became well-thumbed and grubby and this was regarded as being disrespectful. Gradually readers or primers were published specially for schools. These consisted of short passages from what were regarded as ‘improving’ texts, or simple paragraphs which often made little sense. They were read either around the class or a pupil was called to the front to read. Younger pupils read from reading charts.

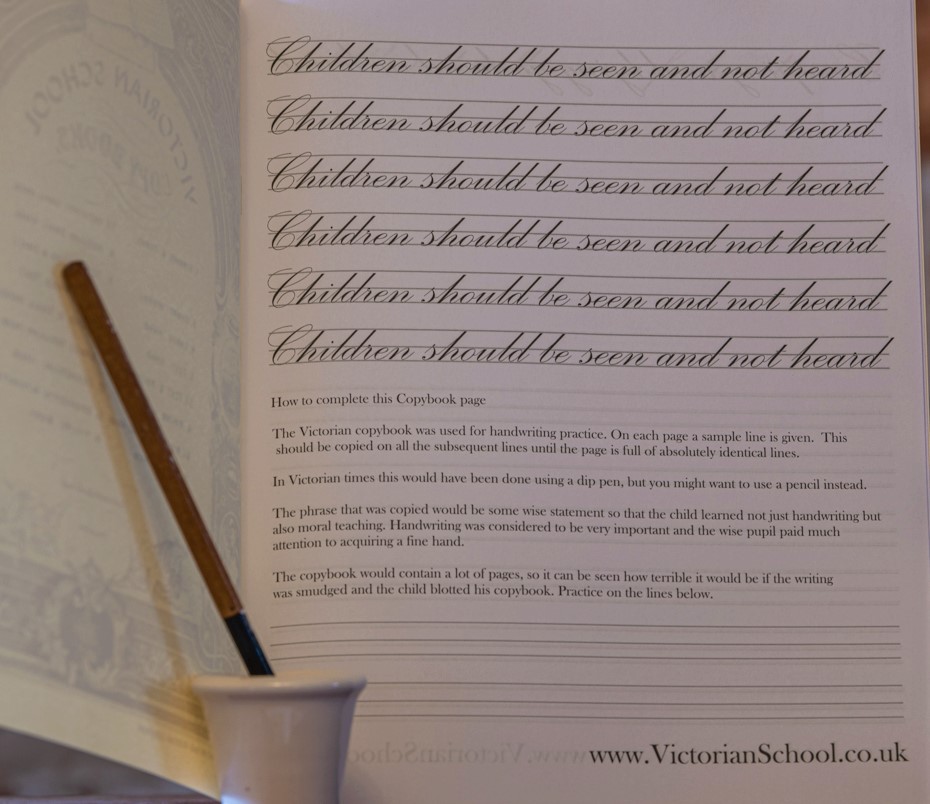

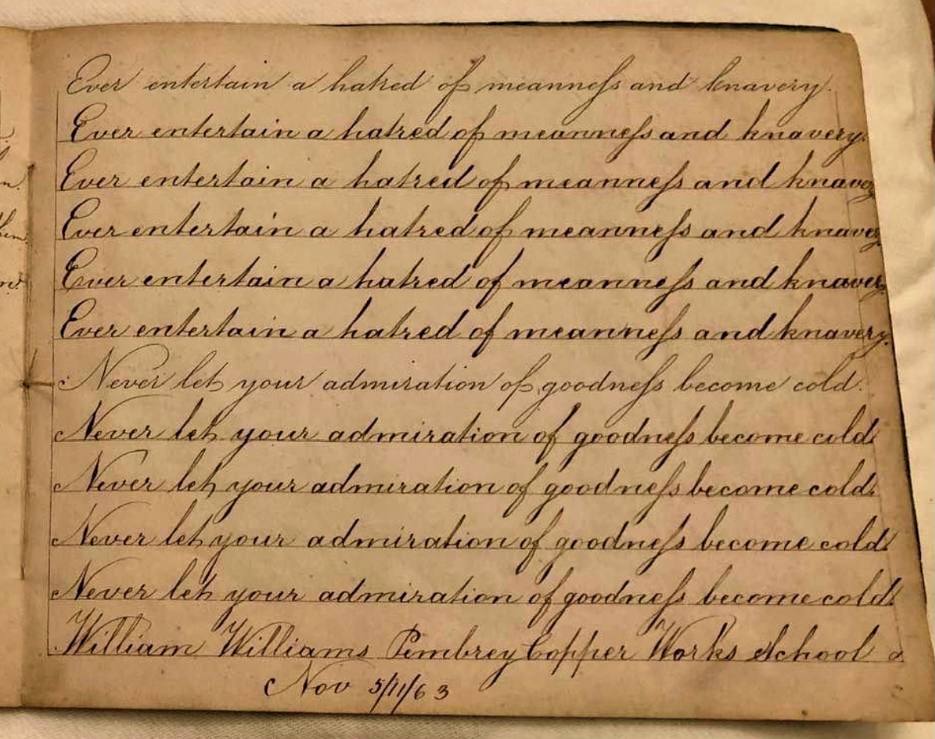

Writing meant handwriting. Paper was very expensive so pupils wrote on slates, the scratching and squeaking of which added to an already noisy schoolroom. Infant pupils practised in sand trays whilst older pupils had a copy book into which they painfully copied moral statements from the blackboard. One example was: “If a job’s worth doing it is worth doing well”. A pupil later remarked: “I wrote endlessly in copy books moral maxims and poems, but I never composed a single original sentence”.

It was the job of the ink monitor to fill the inkwells each morning. When writing in their copy books in copper-plate writing children used ink or dip pens. These didn’t store ink so they had to be dipped regularly in an ink well. This often led to blots for which children were punished – hence the phrase “to blot your copy book”. They were also punished for writing with their left hand which often received a rap on the knuckle. Writing down a dictated passage and learning poems to recite before visitors and the school inspector was also part of the curriculum.

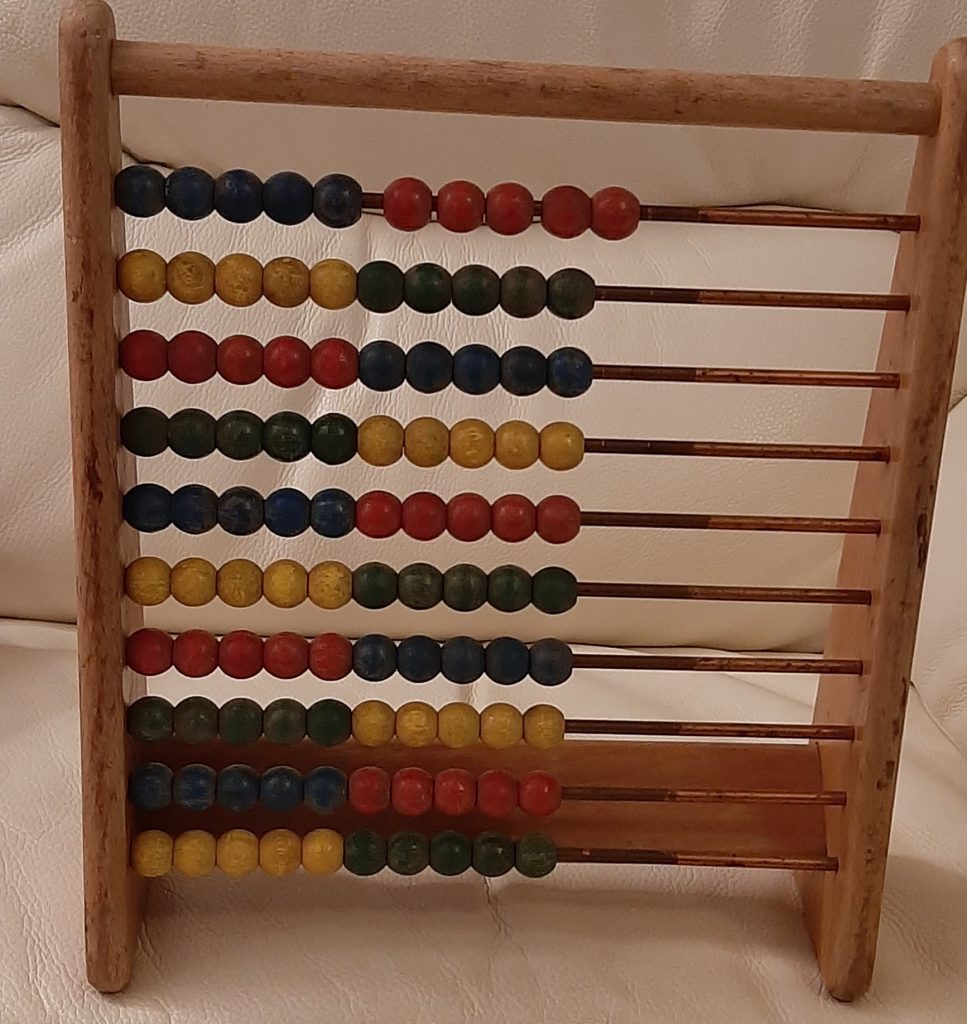

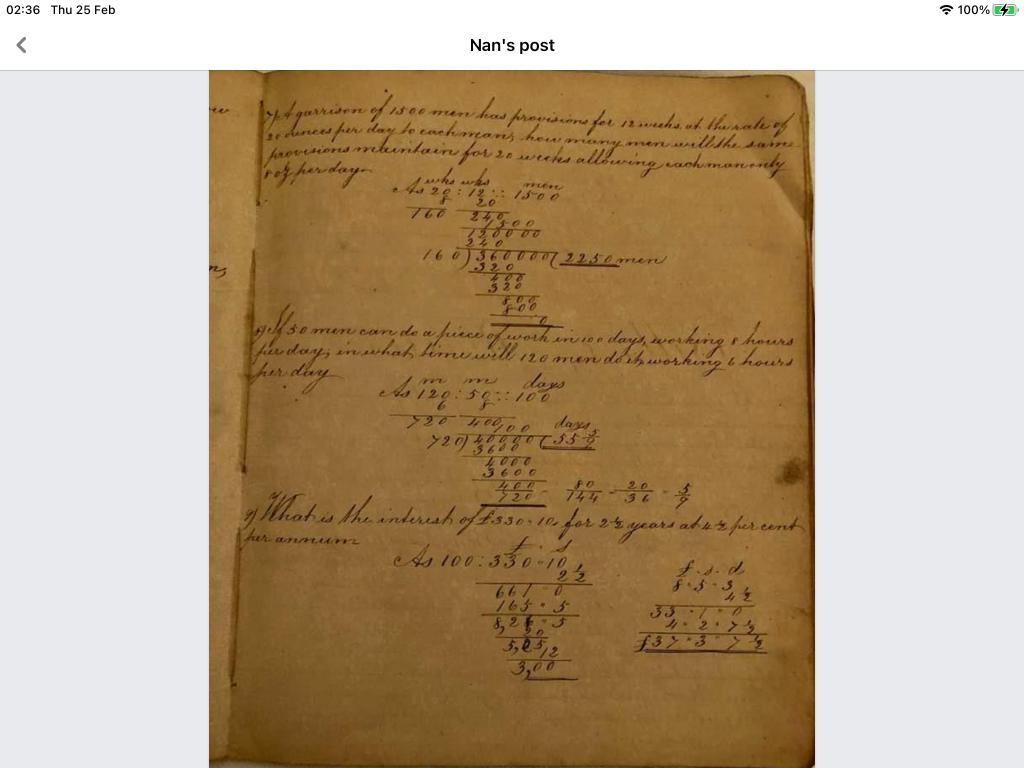

Each lesson normally lasted for 30 mins and there was no morning or afternoon break. In arithmetic lessons pupils were taught to add and subtract, divide and multiply. Pupils started by learning tables which would be chanted every day; sums were copied from the blackboard and worked out on their slates.

The teacher used a large abacus to help pupils with counting and calculations. The teacher or a pupil-teacher would walk around checking the work, which was then rubbed out ready for the next part of the lesson. No work was saved and the pupils were expected to memorize and take in what they had been taught. Bad news for boys – they were often given harder sums to do!

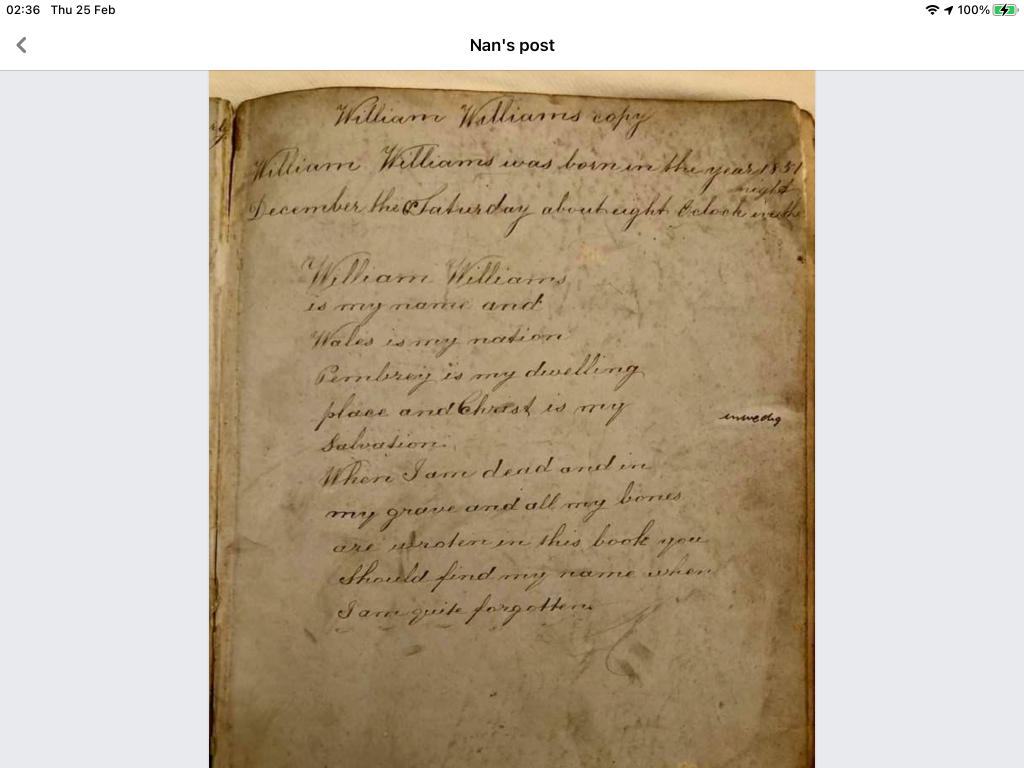

Born in 1852 William Williams was a pupil at the Copperworks School in the latter half of the 19th century here is an example of some of his work. (Photos courtesy Nan Williams)

In the 1870s drill was introduced into schools – “healthy body, healthy mind” was the philosophy. This took place in the classroom or sometimes in the playground. The pupils stood in rows to follow rigid set exercises, raising and lowering arms, jumping with legs astride, and stretching. Sometimes they used dumb bells, as can be seen in the picture.

The object lesson became part of the curriculum to address the criticism of narrow, rote learning and to have a more child-centred approach. It was based on the teaching of Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi (1746-1827) that children learn through senses and “travel from the known to the unknown and from the concrete to the abstract”. In 1882 the Inspector comments, “In future more attention should be given to Object Lessons. Suitable apparatus for this purpose should be provided without delay”. Schools could buy cabinets of objects for these lessons, which included cards with questions to help the children explore the objects.

This is a list of object lessons for Standard 1, taken from the Pembrey Copperworks School Log Book of 1886: Copper, Whale, Oak Tree, Spider, Indigo, Pins, Owl, Cork, Silk, Swallow, Grape, Clock, Eagle, Timber Yard, Snail, Map of the World, Postman, Oyster, Station, Camel.

The object lesson was seen as a good vehicle for teaching science. In Pembrey the boys’ curriculum included religious knowledge, history, grammar, geography, reading, writing, arithmetic, vocal music and mapping. The girls were taught scripture, reading, writing, arithmetic, grammar, geography, sewing, cutting out, knitting, domestic economy.

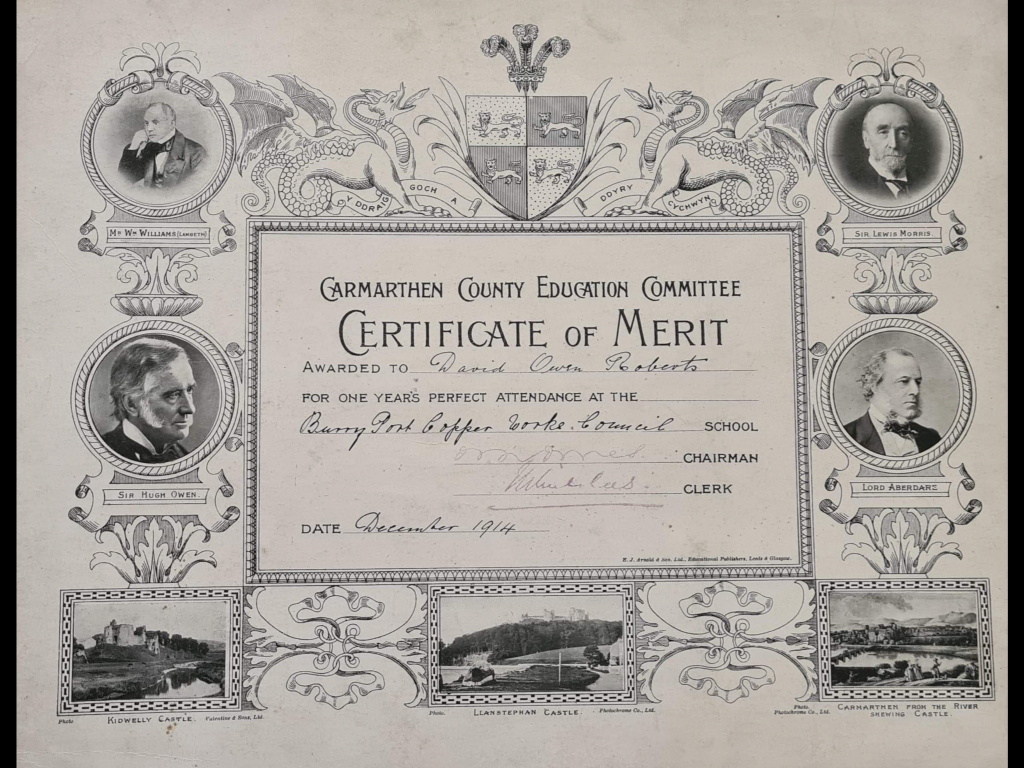

Perhaps the school’s most important event was inspection day when HMIs came to inspect virtually everything in the school. Pupils, often dressed in their best clothes, were questioned by the inspector and the children would also perform poems and songs. Pupil-teachers were also examined in all subjects and given a pass grade that enabled them to progress to the next stage of their career. For many years the awarding of a grant to the school depended on standards and attendance in the school. Pupils were given rewards in the form of certificates for good attendance.

The inspector would also make comments about the buildings and equipment and often made recommendations. For example: a piano was needed for the younger children. In 1893 HMI Report that “the cloakroom accommodation for girls and the closet accommodation for girls and infants is insufficient and should be remedied as soon as possible”.

This was the last entry in Pembrey Copper Works Girls’ School Log Book 1903:

Wednesday 29th July, closed this school permanently at 4.30 in accordance with instructions received from Mr WH Cox (Clerk). Children given a treat in the shape of a tea.

Miss E Williams Headteacher

RESOURCES

- 1. Pembrey Copper Works School Log Books

- 2. The Victorian Schoolroom, Trevor May, Shire Publications Ltd. 1994

Postscript : The Boys’ and Girls’ department along with some of the Infants’ moved to a new school in Stepney Road. Those infant children living south of the railway line stayed as Copper Works Infants’ School until 1992 when all infant children were taught in Elkington Park in 1993.

ELLEN DAVIES June 2021