LAND ARMY GIRLS – A Local Story

On Monday July 12th, 1943 Eleanor James of Silver Terrace in the Bacce, Burry Port received a letter inviting her to begin her training as a Land Girl. Born and brought up in Burry Port, her father had moved to the town from Lampeter between the wars to find work as a miner in the Gwendraeth Valley. Eleanor’s mother, Sarah Griffiths, worked in the Pembrey Copper Works. The family bred whippets and Eleanor turned down a job in an exclusive breeding kennel in Essex to join the Land Army. In the same year she was sent to the farm of John Evans, near Tregaron in Cardiganshire.

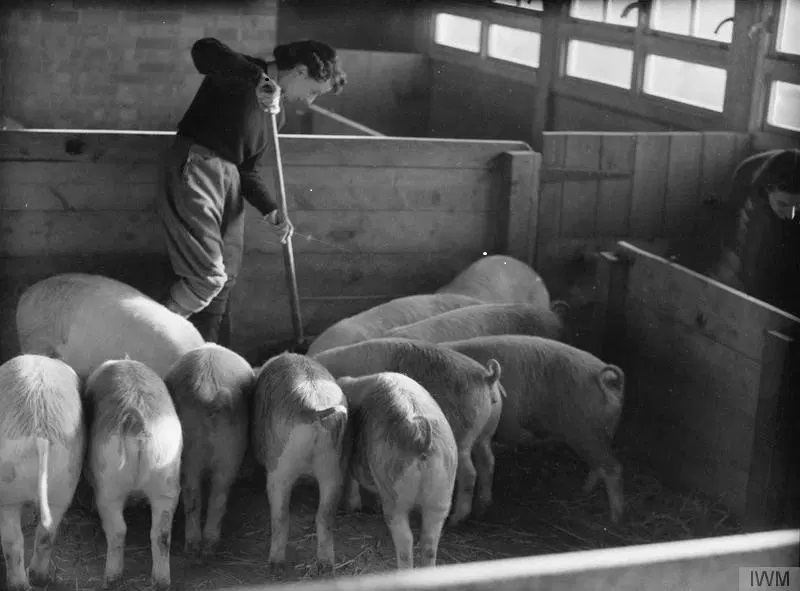

Eleanor was one of a large group of women and girls who joined the Women’s Land Army during WW2 to replace male agricultural workers who had left to join the Forces. She received four weeks training before her placement on a farm. This took place mostly on designated approved farms under the direction of the farmer and would be: one week Pigs, one week Poultry, one week Dairy and one week General Farming. At the end of the period the farmer filled in a report sheet. The quality and degree of training was variable and the girls agreed they learned most on the job.

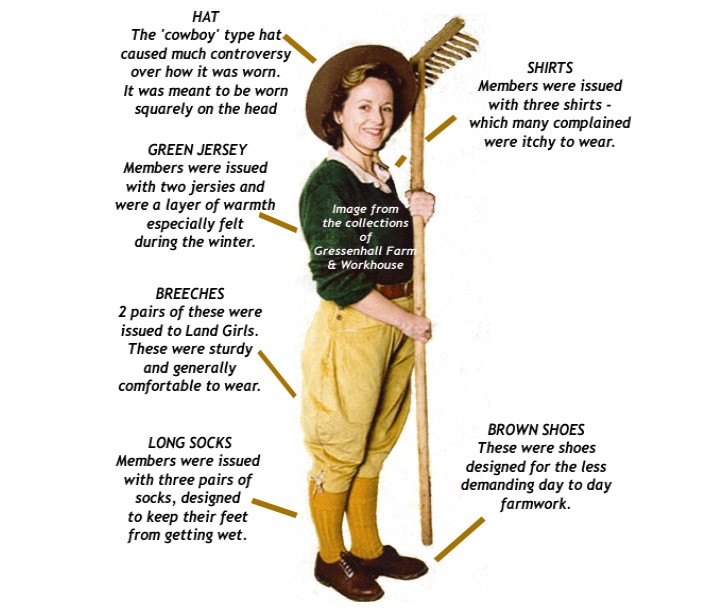

Eleanor had an allowance of about 10 shillings a week and her board and lodging was free whilst she was training. Land Army girls had a uniform which was maybe not as stylish as other service uniforms but was practical and hard wearing. One girl described it as “baggy breeches tied at the knee which made it virtually impossible to bend one’s knees and made you walk like a cowboy who had been on a horse all day”. As had been the case in WW1, Britain did not produce enough food to feed its population and much had to be imported by sea although much of that was lost to enemy attacks. Therefore, in 1917 the Women’s Land Army was formed to boost the production of home-grown food.

Again in WW2 Germany attempted to starve Britain into submission with a blockade. As much land as possible needed to be brought back into cultivation and existing farms needed to be more productive. With men fighting overseas there was a shortage of labour and so in 1939 the Women’s Land Army was revived with Lady Denman, DBE as its Honorary Director. The ages of the girls varied from 18 years to 40 years and girls were recruited from all walks of life – shop and office workers, lawyers, writers and students.

Some girls lodged at farms which were sometimes isolated, but this had some advantages. The farmer’s wife was usually sympathetic and there would be cups of cocoa and crusty bread as well as extra butter, apple pies and eggs to supplement the diet. The other option was living in a hostel (and then bused out daily to farms) where they would have the advantage of the company of other girls – one girl tells of living in a hostel with sixteen others. There they could make their own fun and make light of the hardships, such as hatchet-faced “Witchways” the harridan house-keeper who infamously dished up prunes most mornings for breakfast, telling the girls “to get them down you because you won’t get nothing else”. Another popular food which seemed to be in abundance was beetroot soup, and indeed beetroot in all its guises. One girl, Mavis, stated that most of the girls shuddered at the sight of beetroot for years after.

Land Girls were supervised and their welfare was looked after by a County Secretary who would visit farms and lodgings and deal with any problems. Land Army Girls were employed by individual farmers and not the Government. Farmers made a contract with the girls to work on their farms and they were bound by Ministry of Agriculture & Fisheries Conditions of Employment. Regulations laid down a weekly wage of not less than 32 shillings, and, if billeted in the farmhouse, the girl had to receive a minimum of 16 shillings plus free board and lodge. Girls in hostels and digs were responsible for regularly paying their rent on time.

Whether on a farm or at a hostel there was nearly always a village nearby. Girls fell into bed exhausted by long days, even longer at harvest time, but on the weekend there was time to enjoy what social life there was. In towns and larger villages there would be a cinema, but every village had a village hall where there would be singing and dancing around the piano followed by visits to the chip shop before the long dark walk home. Land Army Girls were not always popular with local girls who would glare at them, especially when the local boys and soldiers at the nearby army camp asked them to dance.

Land Girls did every job imaginable both on the farm and in the countryside. At first they were greeted with suspicion and sometimes open hostility with some farmers often refusing to have them at all. There were no holidays as such: these would have to be negotiated with the farmer. But most farmers were generous and welcoming. One girl recalls the farmer’s wife telling her to throw her sandwiches to the pigs and “come and have dinner with us, love”. Another recalls being given some butter and cheese to take home to her mother in London. But best of all is the tale of Audrey: she was given a rabbit which she packed in a cardboard box and sent to her mother by post. But nobody told Audrey that she had to take its insides out first. The weather was hot and the parcel got delayed and the postman delivered it holding his nose. Audrey’s mum buried it immediately in the garden, so there was no mouth-watering rabbit pie from the farm!

As the war dragged on most farmers came to appreciate and respect the girls many of whom had spent all of their lives in towns and cities and had never seen a cow, let alone be expected to milk one! But they got on with the job and at the end of the war one farmer wrote:

“As you know, I was very doubtful about the wisdom of taking two girls who had had no previous experience. My fears were groundless. They have been quick to learn, and have worked hard at all manner of tasks – not a few of them both dirty and uncongenial. I have nothing but praise for them. They learnt to pitch and load a heavy crop of seeds, and kept the men on the stacks busy until all was stacked. They drove a tractor, harrowed up twitch, which they carted and burned. Had a whole week’s threshing on the corn stacks, taking a man’s place in each case, and keeping pace with the men. They fed and cleaned out the pigs and learnt to milk daily; they picked potatoes and took on four acres of beet afterwards loading it into the lorry. I found them cheerful and willing with never a grumble in rain or storm. Girls like this cannot but help to win the war.”

Most of the girls were sent to work on a mixed farm where work was varied. But there were specialist farms devoted to dairy, where the skill of milking could prove a challenge. One girl reported that she thought the day began with the cry of the rooster, but found the working day day began way before daybreak. Some girls would have to deal with shearing, taking sheep to market and sorting out foot rot. The Land Amy Girls would have training in how to care for the animals, but most of the skills were learned as they went along.

On arable farms girls used tractors and horses to plough and harvest. They were expected to use the machinery with all the attachments as well as combine harvesters. Many girls dreaded the cold, wet winter months when sometimes they needed to use pick axes to dig out potatoes from frozen ground or when they sank into cold wet soil to get out the vegetables. Most Land Girls had never had any experience outside shop or office work and their hands were white and soft. One farmer suggested they rub soil into their hands to harden them up! The early days were the hardest and girls would fall into bed exhausted with aching backs and bleeding, blistered hands, but they soon toughened up and many recalled happy memories.

Land Army Girls also worked in forests and woodlands as the Timber Corps, felling and planting new trees and sawing timber. This required extra training as girls would have to measure and cut accurately and maintain the tools and machinery. They were given the nick name ‘Lumber Jills’. But perhaps the most surprising job for Land Girls was that of pest destruction and they were paid more because it was considered a “nasty” job. The girls called in at farms and were told of any infestations in barns and hayricks. The rats would run out when disturbed, which was a nasty surprise for some. The girls trapped and poisoned mostly rats, but occasionally they were called on to gas foxes and badgers who were also a problem for the farmer.

On some occasions Land Girls and German and Italian POWs worked in the fields side by side. On the whole the arrangement worked satisfactorily and some friendships blossomed into romance and marriage after the war. As the build up to the Normandy invasion began, army camps of international soldiers began to spring up all over the country. The soldiers with the greatest impact were the American GIs. They brought with them gifts of chocolate, cigarettes and silk stockings, and Glen Miller and the Jitterbug caused a sensation in village halls.

When the war ended in 1945 a number of Land Girls stayed on as there was still a great shortage of food and men were only slowly returning to their jobs on the land. The Women’s Land Army, often called “The Forgotten Army” or “Cinderellas of the Soil”, was officially disbanded on 30th November 1950. It is estimated that some 80,000 women joined the Land Army, but they received scant recognition. After much campaigning by the women themselves the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) announced in December 2007 that, in recognition of the efforts of the girls of the Land Army, a special veterans badge would be awarded to surviving Land Girls from July 2008 onwards. In October 2012 the Prince of Wales unveiled the first memorial to the Women’s Land Army of the two World Wars on the Fochabers Estate in Scotland. After a three year fundraising campaign a memorial statue to the Woman’s Land Army and Timber Corps was unveiled at the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire.

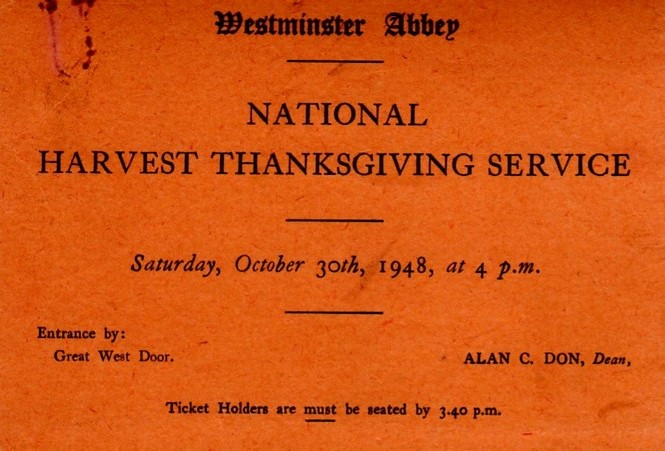

Eleanor’s time as a Land Girl ended on 24th November 1948. She had served nearly six years on a farm in the hills above Tregaron. At the end of her career she was thrilled to receive an invitation to the National Harvest Thanksgiving at Westminster Abbey, where she would form part of the guard of honour. But her proudest moment of all was when the Queen stopped to speak to three girls, one of which was Eleanor. She wrote a full and moving account of her experience both preparing for and attending the service and this account was sent out as part of the national newsletter.

Courtesy Emrys Davies

Every Army Land Girl’s experience was different, but all agreed it was gruelling at first. Yet, despite aching backs, sore and frostbitten hands they had nevertheless laughed and cried together and had great stories to tell. At the end most agreed they had made great friends and had wonderful memories.

After the war Eleanor married Ivor and they lived in Burry Port where they had a son Emrys. Later Eleanor worked at the Cooperative Store in Burry Port.

SOURCES

- Artefacts and archive material of Eleanor James provided by Emrys Davies

- Land Girl, A Manual for Volunteers in the Women’s Land Army, W.E. Shewell-Cooper, 1941, Amberley Publishing.

- Land Girl, Anne Hall, 1993, Ex Libris Press.

- Land Army Days, Knighton Joyce, Aurora Publishing.

- www.womenslandarmy.co.uk

- https://www.peoplescollection.wales

ELLEN DAVIES January 2023