THE KIDWELLY AND LLANELLI CANAL An Overview

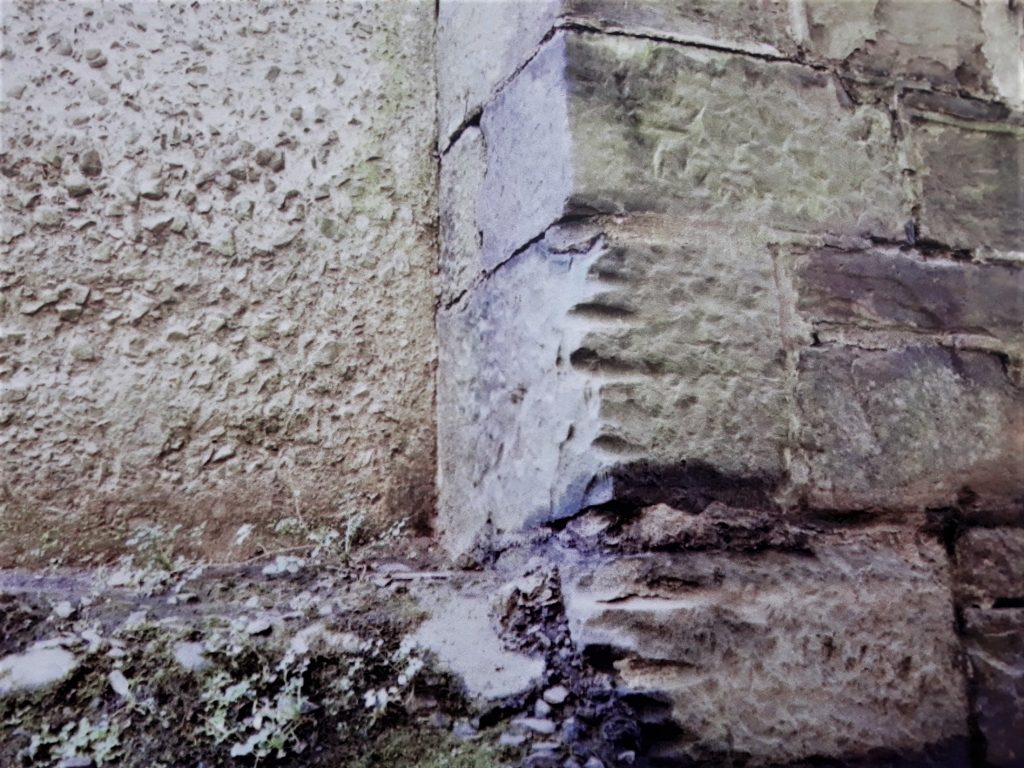

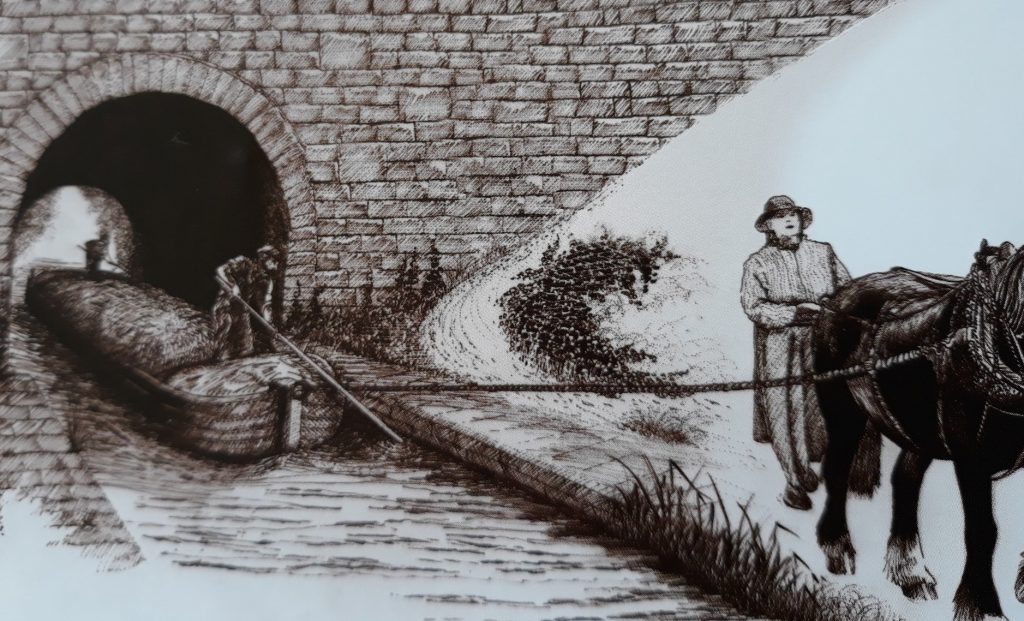

Canals in the 18th and 19th century were important facilitators of the industrial revolution in this area but the lock, the towpath, the barge and the boatman are romantic images long gone. Yet in Pembrey it is still possible to walk or cycle along an attractive section of the old Kidwelly and Llanelli canal and view the gouges made by the tow ropes on some of the bridges. Ironically the canal, despite its name, did not pass through either of the two towns, since it branched south from the existing Kymer’s Canal (the first canal in Wales), cut across Ashburnham’s Canal and made its way only to the new Burry Port Harbour. The spur into the old scouring reservoir or west dock is still visible.

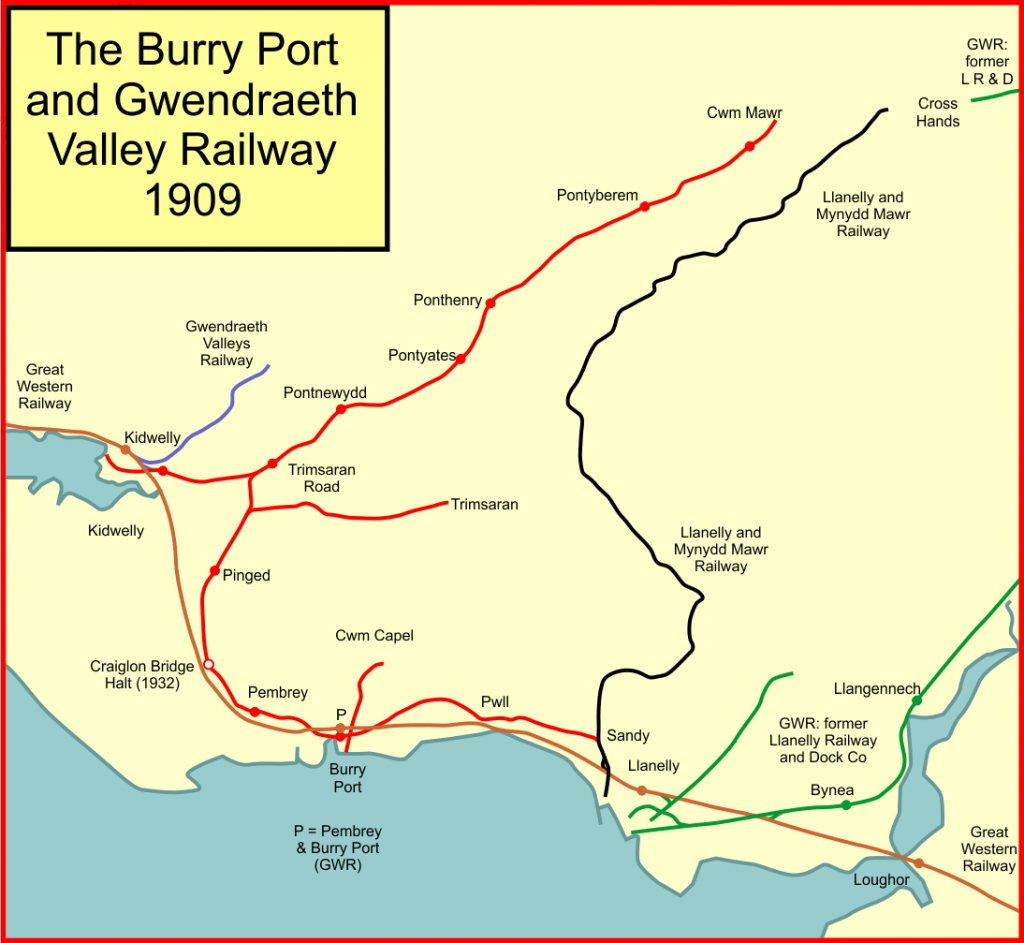

The fragmentary development of the canal is a fascinating mix of vision, ambition, frustration, failure and spectacular success. It was conceived at the Pelican Inn, Kidwelly in 1809 when colliery owners, landowners and members of the Kidwelly Corporation, thwarted by the shifting sandbanks around Kidwelly quay which restricted large boats, sought a way of transporting the lucrative anthracite coal from the Gwendraeth collieries to the sea by means of a canal. The plan was to build a new canal from the end of Kymer’s Canal at Pwll y Llygod (where Thomas Kymer had his collieries) up through the Gwendraeth Valley to Cwm Mawr and down from a junction near Spudder’s Bridge, across the Pinged Marshes and along the coast to Llanelli.

The outcome was an act of Parliament in 1812 in which the newly formed ‘Kidwelly and Llanelli Canal and Tramway Company’ would restore and improve the harbour at Kidwelly as well as Kymer’s Canal, construct and maintain a canal and tramroads which would provide transport of coal from Pontyberem initially in the Gwendraeth valley to the sea at Llanelli. There would also be new bridges and towpaths, feeder canals and tramroads to the collieries and other works along its course. There were some well-known financial backers, including Lord Asburnham, Lord Cawdor and Lord Dynevor and the authorised sum for the construction was £60,000. For land-owners canals brought in extra finance from the leasing arrangements. The venture was based on the view that the market was expanding for anthracite coal with a yield of 10% on the capital sum.

However, progress was slow and finances strained. By 1824 the result was only a stretch of two miles to Pontyates and two miles to the Ashburnham Canal, although the impressive 20 meter long six arched aqueduct over the Gwendraeth Fawr River was completed in 1815. It is not clear what caused such a delay – the possibilities include shortage of money and the decrease in the demand for anthracite. The biggest demand on the money was the work on Kidwelly harbour. At the same time because the traffic flow in the Pembrey Canal and along Gaunt’s tramroads was causing congestion at the Pembrey harbour a new harbour was being planned about half a mile to the east to be called Burry Port harbour. It would have quays, piers, wharves, tramroad connection and a canal link.

Yet in 1832 when the new harbour was declared ready to receive shipping, the Kidwelly and Llanelli canal lay in an almost derelict state. The canal and dock companies had mutual directors and they obtained the services of James Green, a prominent West Country canal engineer. He was made a consultant engineer to the Burry Port docks and produced new and ambitious plans for a much-extended floating dock. These plans would naturally fit in with the canal projections and he was commissioned to review the canal situation and to give a prognosis on how the canal could and should be developed. He was not impressed with the engineering work of Pinkerton and Allen with its misplaced locks and flooding on the towpaths as well as well as the aqueduct and the timber on the bridges decaying. In fact, the canal was at this time largely in disuse. However, Green was later himself to be dismissed for his failures. Working also as a consultant engineer to the new Burry Port harbour he had ambitiously planned a floating dock and scouring reservoir and took this into account when producing his canal plans. These plans included extending the canal in the south to Burry Port, providing a continuous tramroad link from Burry Port to Llanelli and extending the canal from Pontyates to Cwm Mawr which he suggested would provide a cheaper method of transporting coal than the Carmarthenshire Railway. The canal when completed would provide 10 miles of navigable waterway.

The upwards extension to Cwm Mawr was challenging because of the steep gradients and here was Green’s innovation – a small canal with smaller tub barges and three inclined planes which would be half the cost of traditional locks. The Gwendraeth river and a reservoir would provide sufficient water. The inclines would have elevations of 52 feet (Ponthenri), 53 feet (Capel Ifan) and 85 feet (Hirwaunissa) and the estimate of the cost was £35,845. Historians speculate and disagree about how the innovative inclines were managed – water wheels, bucket mechanism, boat lifts, hydraulic pumps, etc. Canal historian Charles Hadfield suggests the clue is Green’s inclined planes in the West Country which were powered by water wheels, counterbalancing or by using the weight of a bucket descending a well. Mining engineer and local historian RG Thomas stated that at Ponthenri the coal was in trams which provided a balance weight. Writing at the time Ap Huw says that “the inclined planes were manipulated by hydraulic pumps which were considered to be great discoveries” which Raymond Bowen thinks is flamboyant reporting and he favours a system of wheeled cradles or trolleys carrying the barges and worked on a counterbalance system.

In 1834 it was reported that the work was well-advanced – banks had been raised, locks demolished and rebuilt or renewed, aqueducts reconstructed, the extension to the new harbour almost completed, the inclined planes well advanced and already 52 small tub barges on the canal system were being used for different purposes. However, unfortunately Green had to admit in October 1835 that the work had stalled since he had badly miscalculated the cost of the engineering work involved. Despite the fact that the inclines were completed not long after he was dismissed his reputation suffered a Jericho moment when the walls of the Burry Port harbour scouring reservoir collapsed.

From 1837, with a cost of £56.000, the canal began to operate successfully and was dredged in 1858 when dividends began to be paid at that time. Yet it met new challenges from the age of the railway and in particular from the Llanelli and Mynydd Mawr Railway which followed in the tracks of the old Carmarthenshire Tramroad Railway and pushed towards Pontyberem. In response, what was a canal company became a railway company and was eventually resurrected in the Burry Port and ‘Gwendreath’ Valley Railway company on the bed or alongside the original canal.

In addition, a tramroad from the harbour provided the link to his furnaces at Gwscwm.

SOURCES

- Morris, W H; Jones, G R (1972). ‘The Canals of the Gwendraeth Valley’, Part 2. The Carmarthenshire Antiquary, Vol VIII.

- Jones, G R; Morris, W H (1974). The Canals of the Gwendraeth Valley, Part 3. The Carmarthenshire Antiquary, Vol X.

- Charles Hadfield, ‘The Canals of South Wales and the Border’, David and Charles, 1960.

- Raymond E Bowen, ‘The Burry Port and Gwendraeth Valley Railway and its Antecedent Canals: Volume 1: The Canals’, Oakwood Press, 2001.

- John A Nicholson, ‘Pembrey & Burry Port: Further Historical Glimpses’, CCC, 1996.

GRAHAM DAVIES November 2022