THE EARL OF ASHBURNHAM’S CANAL (1796-1818)

The Ashburnham Canal was the first of the three canals which followed the success of Kymer’s Canal as coal mining increased to the west of Penbre mountain towards the end of the 18th century. The Ashburnhams were from Sussex and in the middle of the 17th century owned large estates In England and Wales. Their Carmarthenshire estates were mainly acquired through marriage arrangements. In 1677 John, created first Lord of Ashburnham, married Bridget, the only daughter and heiress of Walter Vaughan of Porthamel House, near Talgarth.

It was on the Vaughan’s Penbre estate that Lord Ashburnham first began to mine coal and opened pits at Coed y Marchog and Coed Rhial on the western slope of Penbre mountain. Pack horses were used to transport the coal to the Gwendraeth estuary and also to the Burry inlet. The destination of the coal was mainly the west of England counties and Ireland.

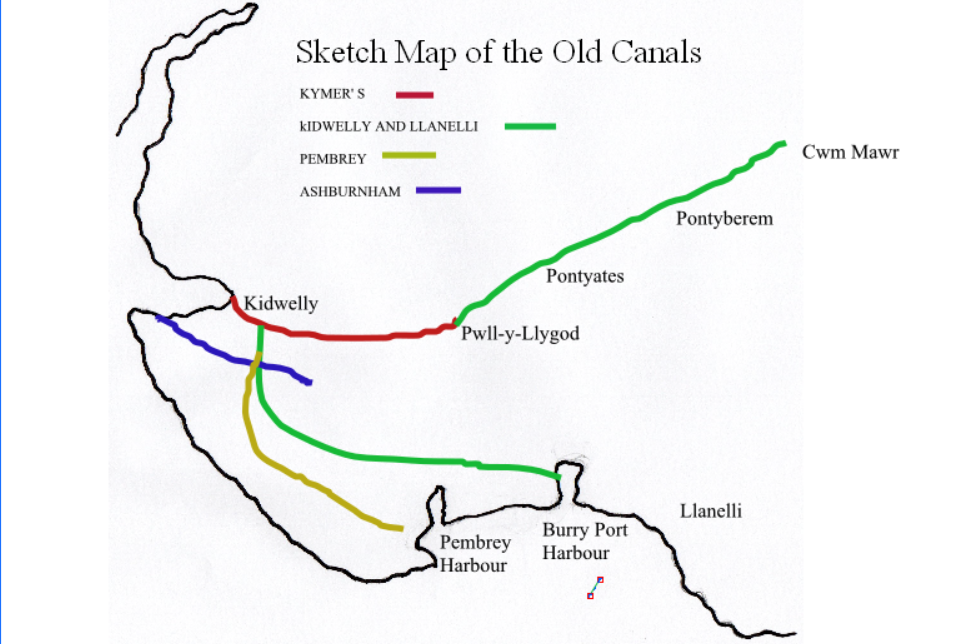

John, the second Earl (1724-1812) suggested building a canal from the bottom of Penbre mountain to the Gwendraeth estuary. He saw the success of Kymer’s canal and wanted to replicate that with an integrated system, although the hauliers objected to the idea since their jobs would disappear. It was in 1796 that the Earl began to make some progress when the first section from Coed farm near the Llandyry-Pinged road was started. The Colliery Account book records for that year indicate a payment of £10.10s. to Griffith Jenkins and Co., for canal cutting, the purchase of barges and the making of a towing path. The canal began at the foot of Pembrey Mountain near Coed Farm and pushed for about three quarters of a mile across the Pinged Marsh towards Pen-y-Bedd, breaching a little further on an old sea defence bulwark and then in 1799 extended into Swan Pool Drain (near Pembrey Airport), fresh water lakes which were incorporated into the canal. The canal terminated on the Gwendraeth Fawr estuary at the fork of a creek Pill Towyn and Pill Ddu where shipping places were built.

The work was difficult since it cut across a tidal marsh with high winds and high tides. The canal was about 2 miles long, with no locks, dug deeply and with high protection ramparts. One local historian viewing a length of the canal, described it as about 25 feet in width with high earthworks and the tow path at such a height that towing would have been difficult in places. Substantial drainage ditches ran at the foot of the tow path bank.

From the basin of the canal in Pembrey waggon roads, some only a few hundred yards in length, were laid to the growing number of levels driven into the mountain, and orders were made for ‘iron rails’, often called ‘plates’, on which the waggons would be drawn. The basin seems to have been a timber construction and there were coal dumps at the mouth of the adits with coal brought to a yard at the basin. The stockpiled coal was stored in secure areas. There was also a yard at Pen-y-Bedd and even after the canal was opened coal was carted from here to the pills indicating that progress to complete the whole canal was slow. Also it seems there was a limited number of barges available. The facilities at the pills were basic and there was considerable wear and tear on the loading banks. Ironically there were times when the water at low tide was little more than a trickle at the pills and at others when the canal with its high banks channelled a rush of water which damaged the banks themselves and the basins. Probably the coal was craned from the barges and then carted on to the waiting ships. Shipments continued to be made up to 1818 with maintenance, repair work, deepening and extending the wharves, although no trace exists today of the site.

However, by this time it was clear that, although the venture was still profitable and the canal well maintained with a new dry dock for the repair of barges, the Pembrey collieries were becoming exhausted. This was indicated by a previous failed investment in two ships to carry the coal from the pills. There was not enough accessible coal to continue the operation and the business needed major new investment and restructuring. Yet heads had already been turned to planning for the restoration of Kidwelly Harbour and extension of Kymer’s Canal to link with the collieries in the Gwendraeth Valley.

GRAHAM DAVIES