The Women of the Royal Ordnance Factory, Pembrey

The ‘Canary Girls’

This article is written to complement the Blue Plaque which will be erected this year at the Information Centre in Pembrey Country Park, on the site of three successive explosives factories, and in particular to commemorate the activities of the ‘Canary Girls’.

Although a great deal has been published on the ROF Pembrey in WW1, and its predecessor in the Stowmarket Explosives Company, very little has been recorded about its activities and role in WW2. More information needs to be gathered to cover these later years.

Introduction

The munitions workers who worked here during two World Wars did so with the two-fold dangers of explosion and ill-health. The munitions workers were mainly women, because most of the young men were either on active service with the armed forces, or were engaged in essential war-time occupations like coal mining, agriculture, railways and construction. Men were mostly called to fight in the armed services, and so girls usually between the ages of 21 to 25 were recruited in large numbers to fill the factories (about 3 million in total) and about a third of them were employed in munitions – manufacturing and mixing explosives, filling shells and bullets.

A Brief History

In 1882 Pembrey Burrows was not populated by trees as it is today, but was a wild, exposed area of grassy sand dunes. It was an ideal location for an explosives factory, well away from habitation, but adjacent to a railway line for importing materials and transporting finished products. It was chosen by the Stowmarket Explosives Company (of Suffolk) to manufacture dynamite for the local mining and quarrying industries, and was settled into the sand dunes which could be used for blast protection. However, within a few months of operation, for reasons unknown, an explosion at the site killed 7 people and injured many others, and so production was brought to an immediate halt.

The site remained dormant until 1914 and the start of the First World War, when it was taken over by the Nobel Explosives Company Ltd, on behalf of the Secretary of State for War, “to erect and manage a Trinitrotoluene (TNT) factory at Pembrey”. In the winter of 1914-1915 construction work began on two factories within the site, one to produce explosives (TNT and the propellant Cordite), and the other being a shell-filling factory, located in the southeast corner.

These factories occupied an area slightly larger than the present site of the Pembrey Country Park, an area roughly equivalent locally to the steel works at Trostre plus the Retail Parks at Trostre and Pemberton, plus Parc y Scarlets, or in national terms, the area covered by Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens. This vast area was needed to disperse the production and storage areas for both explosives and munitions, to minimise and contain any damage caused by fire or explosion.

Following the ‘Shell Crisis’ of 1915, thousands of women were drafted in to munitions with David Lloyd George appointed Minister of Munitions. TNT was in short supply and was expensive to produce, so Amatol was developed, which was a mixture of TNT and Ammonium Nitrate.

By 1918 the explosives factory employed almost 5000 people, of which 60% were women, with workers transported by train to special ‘halts’ constructed near the site: on the GWR main line at ‘Lando’ and also on the two branch lines into the site. Workers were recruited from the surrounding areas of Llanelli, Carmarthen and Swansea, while buses brought workers from outlying areas.

After hostilities ceased and until the end of 1919 workers at the Filling Factory were employed in disassembling munitions, following which the plant and machinery were sold off to breakers and scrap merchants, leaving behind a scene of post-industrial dereliction.

After WW1

As a consequence of women’s involvement in the war effort, in munitions, agriculture and industry, the suffrage movement gained greater strength. This resulted ultimately in women being granted the right to vote, to enter parliament and be given other freedoms and rights.

Between the wars, especially during the Depression, the administrative buildings at Pembrey were used as a school camp for under-privileged children and families, particularly those unemployed.

In 1938, in preparation for the likelihood of war, the site was cleared of all remnants of the former works, and a new factory was constructed at Pembrey, occupying the area of the present Country Park. Production began in December 1939 and at its peak employed 3000 workers.

Working Conditions

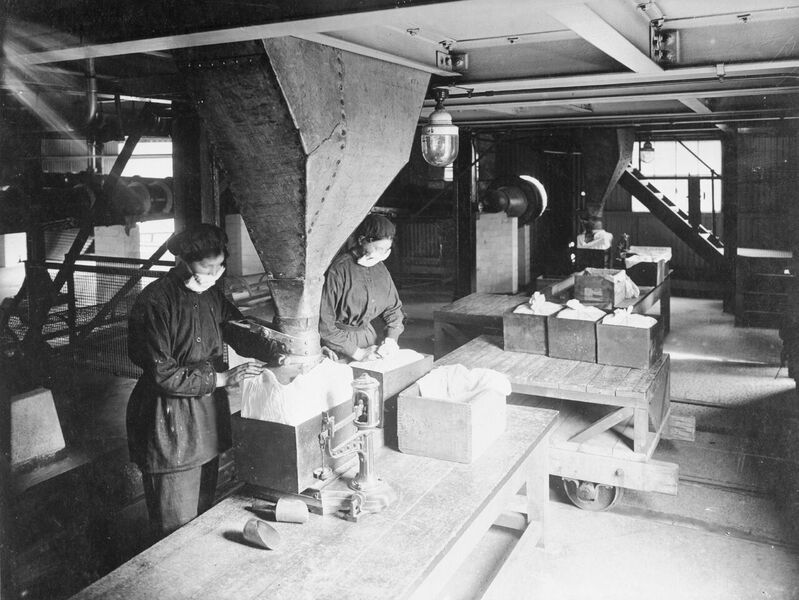

TNT is poisonous: contact with the skin causes irritation. The chemicals responsible for yellowing were the explosive TNT and the cordite propellant. The chemicals reacted with melanin in the skin to cause yellow pigmentation, giving rise to the girls acquiring the nick-name ‘Canary Girls’. Other side effects were nausea, caused by inhaling dust and fumes, and also the skin condition ‘hives’. Some were known to have developed epileptic fits. [Research carried out by Dr Helen McCartney (Kings College London) revealed that some women during WW2 gave birth to bright yellow babies (“Canary Babies”) . ]

It was known that these chemicals and the working conditions were injurious to health but filling by hand was the only way possible and skin contact and inhalation were inevitable. The consequences were inflammation of the skin, the respiratory tract and digestive system. Away from this environment these effects would fade over time, but in a small number of cases, such exposure led to liver toxicity, anaemia and jaundice, which could prove fatal. The skin effects gradually faded away, but the girls accepted that this is what happened, and they took it for granted. There was a risk of losing fingers or hands, burns and blindness. They would take the casing, fill it with powder through the top opening using a scoop: the powder would be compacted, and finally a detonator put in the top and tapped down. If they tapped too hard, it would explode. Turning yellow was the least of their problems.

The diary of Gabrielle West gives a fascinating insight into working life at Pembrey. Originally from Gloucestershire, the daughter of a vicar, she was recruited into the Women’s Police Service and posted to Pembrey. Her task was to conduct searches for prohibited articles – anything that would produce sparks or fire (metal objects, matches and cigarettes, even umbrellas and hairpins!) – but also food which might contaminate the explosives. Gabrielle was also involved in site security and discipline amongst the girls. She wrote:

“The ether in the cordite affects the girls. It gives some headaches, hysteria, and sometimes fits. If a worker has the least tendency to epilepsy, even if she has never shown it before, the ether will bring it out… On a heavy windless night we sometimes have 30 girls overcome by fumes in one way or another…”

“The factory is very badly equipped as regards the welfare of the girls. The changing rooms are fearfully crowded, long troughs are provided instead of wash basins and there is always a scarcity of soap and towels. The girls’ danger clothes are often horribly dirty and in rags…. There were until recently no lights in the lavatories and as these same lavatories are generally full of rats and often very dirty, the girls are afraid to go in.”

“The TNT stinks; no other word describes it – an evil, sickly chokey smell that makes you cough until you feel sick.”

However even this was not as bad as in the acid section, where (Gabrielle West continues) “the air is filled with white fumes and yellow fumes and brown fumes. The particles of acid land on your face and make you nearly mad with a feeling like pins and needles, only more so, and they land on your clothes and make brown spots all over them, and they rot your hankies so that they come back from the laundries in rags, and they get up your nose and down your throat and into your eyes so that you are blind and speechless by the time you escape…”

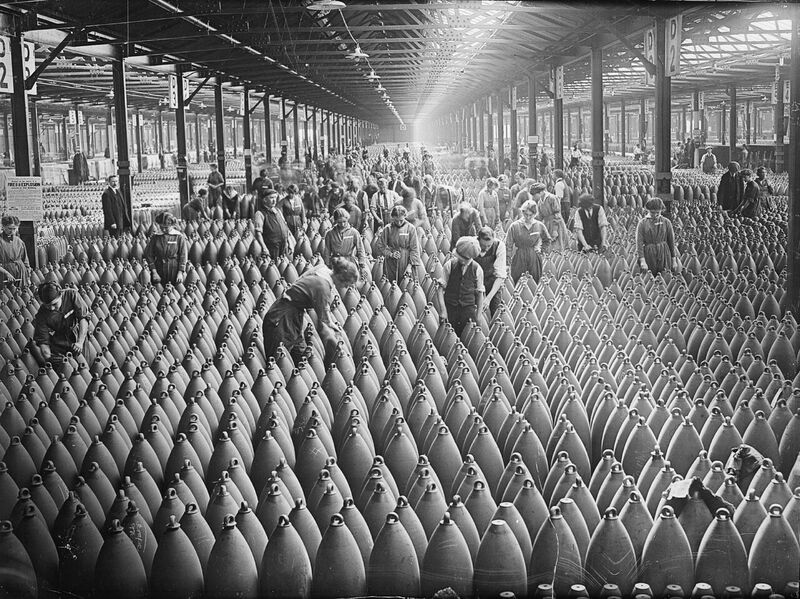

The shell consists of three components – the base, with the propellant, (guncotton ruined the guns so Cordite was invented), the casing containing the high explosive, and the cone containing fuses or the striking pin for detonation on impact. All three had to be fitted together in the Filling Factory. At its peak, in the Filling Factory, over 200 tons of TNT were used every week, filling shells, torpedoes and mines. At the Filling Factory, there were over 1000 workers by 1917, 70% of whom were women, and in the last two years of the war Pembrey exported over 1 million shells from the Filling Factory to the battlefronts.

The large site at Pembrey was divided into different areas. The cordite preparation buildings were surrounded by earth banks, and had brick tunnels leading into them. Storage areas were needed for incoming shells or gun cartridges and also for ammunition boxes. The magazines for storing completed munitions were structures surrounded by earth and sand bunds for blast protection. There were dozens of them distributed around the site, each served by a narrow gauge tramway.

ROF Pembrey WW2

The site at Pembrey during WW2 was one of several ROFs making TNT but it is thought that Pembrey was the biggest in the country. In addition the site made tetryl and ammonium nitrate. At the time of writing it is not certain that Pembrey was a Filling Factory at this time, but simply a producer of explosives for filling elsewhere.

Little has been recorded about the working conditions at Pembrey during WW2, so some evidence can be gleaned from other similar sites.

There were two large ROFs in the west of Britain – Rotherwas, south of the city of Hereford, and Bridgend, in the Vale of Glamorgan. A great deal of research including personal histories has been carried out for both sites. Rotherwas was a Filling Factory, while Bridgend carried out all manner of operations. Pembrey, as a large producer of TNT, would have supplied both of these sites.

Bridgend was built specifically for WW2, and was the biggest munitions factory in Europe, employing 40,000 people at its peak. It is more than probable that all the filling in South Wales was carried out there.

At Bridgend the girls operated a 3-shift 24 hour continuous system. The site was so large that once workers had passed through security and body searches at the gates , they were then bussed to their various sections. The searches were conducted to prevent contamination of the site and the ammunition. Bringing in food was banned so adequate canteens were provided. A thorough clothing check was needed, looking for metallic parts – anything that could cause a rogue spark.

Conscription for girls began in 1940, and they were given three choices: armed services, land army, or working in a government factory – in this case munitions. There was no compulsion over the choice. Girls were recruited from the Valleys, Cardiff, Swansea and surrounding areas, arriving by train at a special halt at Pencoed . The pay in munitions was good – up to £3 per week with meals and transport provided, for a 45 hour week. In the Land Army, by contrast, the pay was £1-8s (£1.40) for a 50 hour week, with half of that being deducted by the farmer for food and accommodation. The other benefit of working in munitions (as in Bridgend and Pembrey) is that people could continue to live at home, whereas in the Land Army they probably could not. (An interesting side-story is that a dormitory village was built at Island Farm near the site at Bridgend, but was largely unused as the girls preferred to travel home. After D-Day the site finally found a use as a prisoner-of-war camp, later accommodating 200 German officers awaiting trial at Nuremburg, including Von Rundstedt.)

The shift system disrupted family and social life but this was compensated by the strong camaraderie amongst the workforce. The money was a strong incentive, and again people felt that it was a patriotic act, that they were ‘doing their bit’ for the war effort. Most families had someone who was on active service – a brother, cousin or uncle – and this was a means of showing involvement and support. Whatever dangers existed, people were able accept them as part of that effort.

In Rotherwas during WW1 there were 6000 staff, 4000 of whom were women. In WW2 there were 8000 staff, mainly women. In recent years, after a local campaign for recognition, 31 Herefordshire women and one man were awarded badges at a ceremony in the county and were later entertained by Theresa May at 10 Downing Street. A plaque was then unveiled at Rotherwas in October 2017. There was constant danger from bombing as these sites were prime Luftwaffe targets.

Pembrey after WW2

At the end of the war Pembrey continued to make TNT and tetryl for military use, and ammonium nitrate for use as a fertilizer in agriculture. There was a resurgence of activity during the Korean War (1950-1953).

From 1944 Pembrey undertook the breakdown of surplus ammunition, mainly 4.5 inch shells and 500lb bombs. Again it was mostly young women who were exposed to these hazardous materials on a daily basis.TNT had to be steamed out of the shells – it dissolves in water with a melting point of 800C. The material was then stacked and burnt, away from the buildings, on what became known as the ‘burning grounds’. The extraction from twenty shells would be burned together, which in winter time would light up the sky. The site closed at the end of 1954

Pembrey : Casualties of WW1 and WW2

- July 1917: an explosion kills 6 people.

- November 1918: an explosion kills 3 munitions workers from Swansea while disassembling a HE shell.

- July 1940: a German plane drops several bombs and 10 workers are killed.

- November 1941: two men were killed by an explosion in the mono-nitration plant and two men were awarded the British Empire Medal for bravery in averting further injuries and damage.

No-one will ever know how many other accidents there were at Pembrey because of the lack of records. For accidents serious enough to warrant an investigation or public enquiry or inquest there were reporting restrictions in national newspapers and a deliberate vagueness in details.

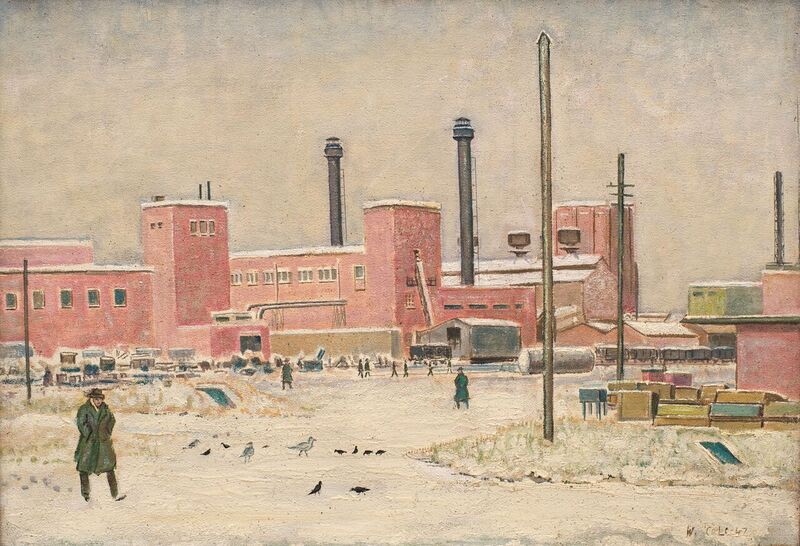

In Parc Howard Museum (Llanelli) there hangs a painting entitled “Our Factory in Winter”. The inscription reads: “Presented to R O Bishop Esq MBE Assistant Director of Ordnance Factories by his colleagues and friends in the Explosive Group 31st May 1952”.

The artist is Walter Stevens Cole, and the painting depicts part of the works at ROF Pembrey in the severe winter of 1946/1947. The painting is dated 1947 and was probably painted in the January of that year when the snows in the UK were at their worst, when even somewhere with as mild a climate as Pembrey felt the effects. You will note that there are no vehicles in the painting and it was the snow which captured the artist. Cole was an amateur artist who regularly exhibited with Llanelli Arts Society. A plasterer by trade, his deep passion for art made him a fascinating character and his home in Als Street a focal point for Llanelli artists.

Bibliography

- The History of the Pembrey Royal Ordnance Factory, Llanelli Borough Council (undated)

- ‘Manufacturing Munitions at Pembrey during Two World Wars’, Alice Pyper, Carmarthenshire Antiquary Vol 53 2017

- ‘An Explosive History’, David Hughes, Llanelli Miscellany

- Pembrey Country Park: Discover a hidden history – Carmarthenshire County Council publication

- ‘Homefront Heroines’ – Will Hayward. Llanelli Star 13/2/2019

- ‘Women, Wales and War’ – Women’s Archive of Wales (online)

- ‘Three Pembrey Explosives Works’ – John A Nicholson, Book Four ‘Historical Events and Recollections’.

- ‘The Rotherwas Project’ – BBC Radio Herefordshire

- ‘Bridgend ROF Research Project’ – website

- “Canary babies” – Dr Helen McCartney, Kings College, London

Footnote: Where does the title ‘Royal Ordnance Factory’ come from?

The Concise Oxford Dictionary tells us that ‘ordnance’ is ‘mounted guns and cannon, and materials and stores dealing with the same’. So the manufacture of the chemicals needed for explosives and the shells and bullets all come under this heading. Hence the term ‘ordnance factory’.

The term ‘ordnance’ crops up again in today’s maps produced by the Ordnance Survey. These too have a military origin. During the Jacobite uprising in the Scottish Highlands in 1745 the British Army desperately needed detailed, accurate maps as none were good enough with which to locate and target the dissenters (for ordnance purposes) . Then later, due to the vulnerability of the south coast from invasion by the French, maps were produced for southern England. Likewise maps of Ireland followed in the 1830s. Thus the Ordnance Survey was formed, which we have today, though now it is an independent private commercial company wholly owned by the government.

ROGER WILLIAMS August 2021