The Copper Industry and the Slave Trade

We have been reminded recently of how imperialism, colonialism and, in particular, the slave trade has impacted on our history and heritage. Indeed, much of what we see around us will have had some kind of link to these factors.

Chris Evans in his book ‘Slave Wales’ shows how it was Wales that revolutionised the copper industry in the 18th century. Spearheaded by Welsh copper producers, largely those in the Swansea area, 41% of the global output by the end of that century was smelted in Wales. We have been sadly long aware that exports to African markets were closely linked to the slave trade. For example, the West Indian rum and sugar plantations needed copper vats and containers, and manillas (horse-shoe shaped bangles) and copper rods were used as currency by the slave traders. For that purpose Swansea’s White Rock works had a manilla house.

It is clear that some of the main players in the local copper trade were slave owners. Pascoe St Leger Grenfell of Swansea copper smelters ‘Pascoe Grenfell and Sons’ was awarded with his partners the compensation payment of £4121 for the enslaved people on Hazelymph in St James (216 slaves), a sugar plantation in Jamaica. In addition he was an unsuccessful claimant for the St Elizabeth estate in Jamaica with 131 slaves.

The same claim involved Rees Goring Thomas of a local land-owning family after whom is named Goring Road in Llanelli. His partner James Esdaile of ‘James Esdaile and Sons’, London Bankers, was also a slave owner with 216 slaves on the Jamaican Rose Hill Estate.

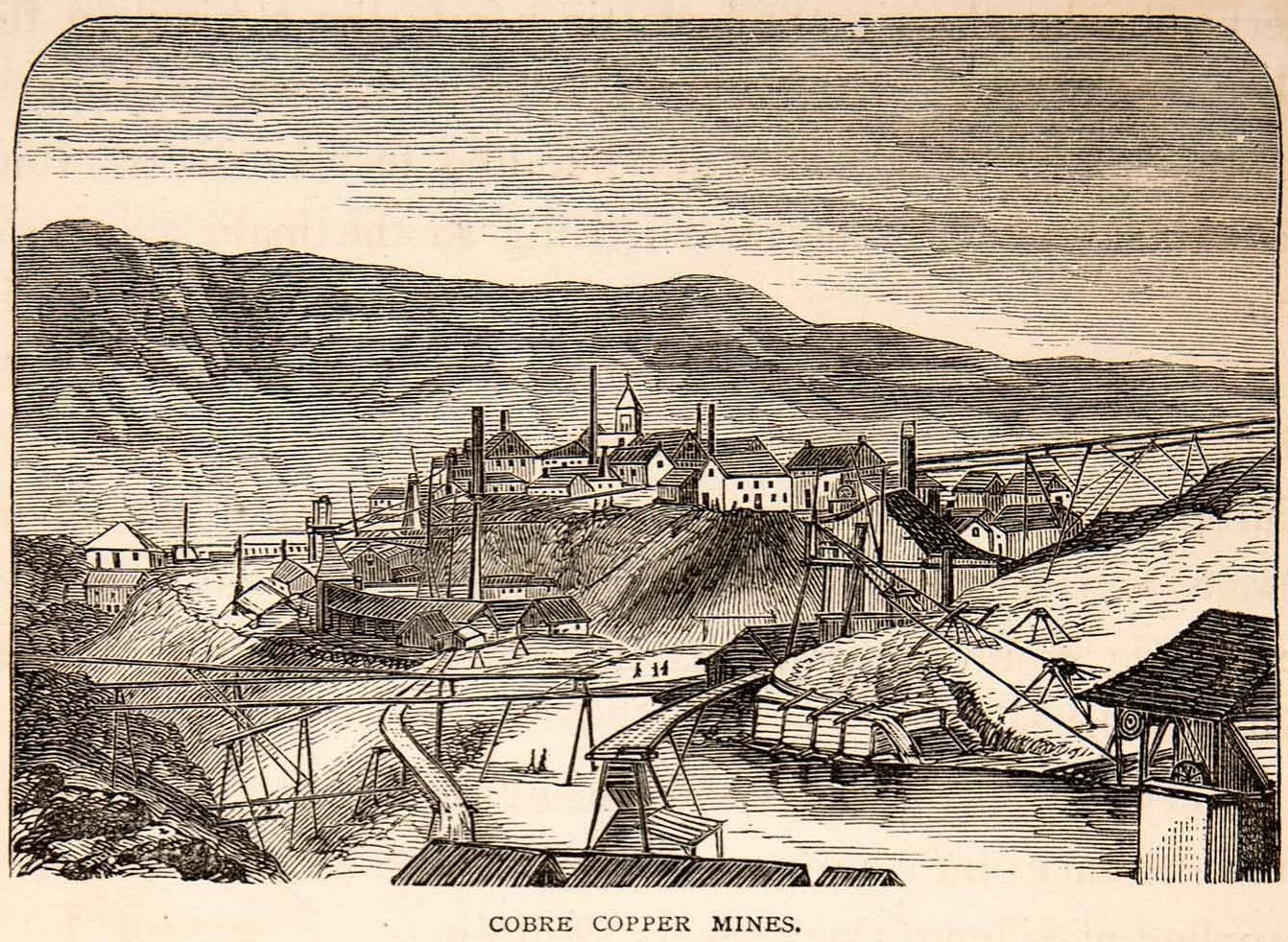

The local Llanelli and Burry Port copper industry links with the slave trade are perhaps less well-known. In 1830 the London based English Copper Company established the Cambrian Works in Llanelli. The background of the directors is illuminating. We know from the legacies of British slave-ownership that a number of them were slave owners with plantations in Barbados, Grenada and Demerara. The proprietors of the Cambrian Works were ‘Mary Glascott and Sons’. Glascott with her sons George and Thomas were brass founders in Whitechapel London and in July 1835 (after Britain abolished slavery in most of its colonies) joined with a group of partners to form the ‘Company of Proprietors of the Royal Copper Mines of Cobre’ with a head office in London. An indenture, kindly shared with me by Chris Evans, names as the proprietors Mary Glascott, George Glascott, Thomas Glascott along with a breathtaking array of slave owning families including Rees Goring Thomas, Pascoe and Riversdale Grenfell and others living in Cuba with slave owning links to Trinidad and Antigua. The group’s auditor was solicitor Alexander Druce who was a partner in the Llanelly Copperworks Company. Despite the London addresses the company ‘signalled the formal absorption of the Cobre mines into the Welsh copper industry’ (Evans).

Copper mining at El Cobre, on the Sierra Maestra in the south east of

Courtesy WikiMedia Commons

Cuba, stretched back to the sixteenth century. The new company reopened the disused mines abandoned by the Spanish and it was Cornish miners who first provided the technological and labouring workforce at El Cobre. Their earnings were high but the conditions were poor. In a humid climate and accommodated in flimsy houses with no protection from flies and mosquitoes, their numbers were depleted by yellow fever to such an extent that reinforcements from Wales (paid less than the Cornish men) were introduced and then ultimately the company resorted to African slave labour.

Despite the 1830s being the decade of slave emancipation it is not so surprising that a company led by so many slave owners would be open to slave employment. In 1841 the number of workers had risen to 750, 64% of which were slaves. It seems the treatment of slaves was no different from that experienced in the West Indies. Diary extracts from Cornish miners, who were shocked at the brutality, reveal a savage regime of beating, flogging and torture. The combination of British capital, Cornish and Welsh expertise and labour resulted in the transformation of El Cobre. The company’s growth was phenomenal with shares being exchanged at £40 apiece on the London market and a monthly profit of £12,000.

At Swansea there were three main wharves for copper ore, all in the North Dock. They were managed by Henry Bath & Sons, (Bath’s Yard or Trelandwr Wharves); Richardson & Co.’s (Cobre Yard) and Thomas Elford (North Dock Wharf). At the wharves the ores were sampled and assayed (analysed to determine the content) and then sold two weeks later at an auction. It was attended by all the local copper masters. Listed among the companies that bought copper ore regularly in the auction from El Cobre is the Elkington and Mason copper works of Pembrey and Burry Port.

There is a detailed description by an observer of what took place at such ‘ticketings’: The proceedings were remarkable for the total absence of any excitement and, at a long table, arranged with blotting paper, pens and ink, the proprietors or agents of the copper works take their seats. The buyers would have had previously each lot they were interested in assayed and they entered on a small billet of paper the amount they bid per ton for each lot, folded the paper and handed it to the chairman. He then announces the buyer and the ‘excess’ – the sum per ton by which the buyer’s bid exceeds the nest highest bid.

Records of the sale of copper ore at Redruth in Cornwall and Swansea in the 1860s reveal that ‘Mason and Elkington’, as they were listed, were purchasers from a number of Cornish mines as well as Berehaven (County Cork), Wheal Maria (Devon), Kanmantoo (Australia), Worthing (Australia), Chili, Knockmahon (County Waterford), South Africa and and El Cobre in Cuba. For example, on 28th July 1963 at Swansea Elkington and Mason bought 86 tons of El Cobre ore as well as well as 100 tons from Berehaven. In the same year on 11th August they bought 92 tons from El Cobre, on 17th November 60 tons and in December another 48 tons.

Complicity was widespread in South Wales both in the El Cobre project and in the other links between the copper industry and slavery. It mirrors to some extent the dark British national picture of slave ownership which resulted in vast personal fortunes and huge profits from unbelievable suffering. Yet it should not be hidden and it needs recognition of this and the historical attitudes to race that accompanied slavery if we are to properly understand our heritage and reflect on it.

Resources

- ‘Slave Wales: The Welsh and Atlantic Slavery, 1660 – 1850’ , 2010, Chris Evans

- Mining and Smelting Magazines, 1862,1863,1864,1865

- ‘Labour and the Poor in England and Wales, 1849-1851: The mining and manufacturing districts of south Wales and north Wales’, Jules Ginswick, 1983.

Graham Davies August 2020