JAMES GREEN – HERO OR VILLAIN

Local history books differ in the attention and importance they give to the renowned civil engineer James Green. Some give little more than a few sentences to his contribution to the Burry Port Harbour and canal system; others spend pages discussing his involvement. This article is a reassessment of his profile in Burry Port. Much of the information of his career up to 1832 is owed to the biography written by Brian George.

JAMES GREEN’S ENGINEERING CAREER TO 1832

Born in 1781 in Birmingham, Green gained his early experiences in the field of engineering from his father who was a civil engineer and contractor in Warwickshire and the nearby counties. Of huge significance was his employment by John Rennie, one of the greatest civil engineers of the time. Rennie used him as his assistant on surveys, canal works and the drainage of bogs and fens. He allowed him to lead on an early project in the reconstruction of the sea lock of the Chelmer and Blackwater Navigation, which was the canalisation of the Rivers Chelmer and Blackwater in Essex.

He worked with Rennie for one year in Devon in 1806 on a number of schemes including ways of improving the navigation of the River Dart below Totnes bridge and the construction of Plymouth Breakwater.

At the age of 27, following the collapse of the newly rebuilt Fennny Bridges near Honiton, Green successfully contracted for the design and construction of a replacement bridge with three spans, and as his reputation spread he was asked to improve and construct other Devon county bridges leading to his appointment as County Surveyor and responsibility for over 230 bridges.

Land Reclamation and Architecture

In 1813 he was commissioned to reclaim at Budleigh Salterton in the estuary of the river Otter an area of over 140 acres after it became vulnerable to flooding at high tides. In 1810 he took on a prestigious architectural assignment by transforming Buckland House, damaged by fire in 1798. He was praised as “an accomplished innovative practitioner in the neo-classical style”. Buckland

Green turned his attention to the development of turnpike roads and submitted a number of proposals for realignment to eliminate steep inclines, increase widths and improve surfaces for the safety for horse drawn vehicles. They involved a number of different features leading to 14 miles of road improvements. Turnpike

Brian George sums up Green’s achievements by 1820: at the age of 39 James Green had established himself as a county bridge surveyor with many fine bridges to his credit; he had proved his expertise in the reclamation of land and as an impressive architect at Buckland house and St David’s Church; as a highway engineer he had initiated a series of schemes with his proposals for turnpike roads; he was now about to embark on a career as canal engineer.

Green’s work on canals developed from the construction of the Bude canal which involved substantial engineering works. A sea lock was built and the improved version is still in use today. Full size barges were used from the harbour basin and then his use of tub boats for the six inclined planes was innovative and the work also included a dam and a reservoir. The inclined planes were the feature that defined his work from this point on. The tub boats were hauled up and let down the inclined planes by chains which were operated in five of the cases by waterwheels. However, one of them (at Hobbacott) used a huge bucket filled with water and this pulled the ascending tub boat up the incline. This innovative procedure worked well in this canal but the use of inclined planes and lifts were not so successful in Green’s design in the Grand Western Canal.

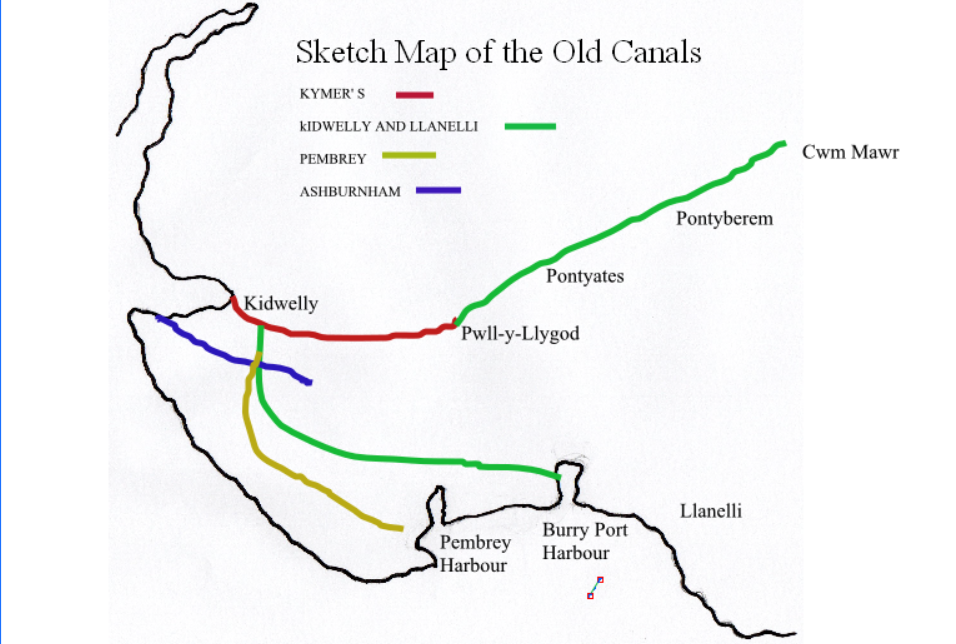

THE CANAL WORK IN BURRY PORT AREA

In 1832 when the new Burry Port Harbour harbour was declared ready to receive shipping, the Kidwelly and Llanelli canal lay in an almost derelict state. The canal and dock companies had mutual directors and they obtained the services of James Green who was made a consultant engineer to the Burry Port docks and produced an ambitious plan for a large floating dock.

These plans would naturally fit in with the canal projections and he was commissioned to review the canal situation and to give a prognosis on how the canal could and should be developed. He was not impressed with the engineering work of Pinkerton and Allen with its misplaced locks and flooding on the towpaths as well as over the aqueduct and the timber on the bridges decaying. In fact, the canal was at this time largely in disuse. His plans included extending the canal in the south to Burry Port, providing a continuous tramroad link from Burry Port to Llanelli and extending the canal from Pontyates to Cwm Mawr which he suggested would provide a cheaper method of transporting coal than the Carmarthenshire Railway. The canal when completed would provide 10 miles of navigable waterway. Historians disagree about how the innovative inclines were constructed but most probably the methods Green had used in Devon were replicated here.

In 1834 it was reported that the work was well-advanced – banks had been raised, locks demolished and rebuilt or renewed, aqueducts reconstructed, the extension to the new harbour almost completed, the inclined planes well advanced and already 52 small tub barges on the canal system were being used for different purposes.

However, Green unfortunately had to admit in October 1835 that the work had stalled since he had badly miscalculated the cost of the engineering work involved. Despite the fact that the inclines were completed after he was dismissed his reputation suffered.

THE DOCK WORK

There seems to have been three phases in the planning which eventually resulted in the completed harbour.

The first involved tenders and plans from John Wedge and Samuel Bowser, son of George Bowser. The outcome in 1832 was essentially a larger version of the old Pembrey Harbour – a tidal harbour with a western pier and an eastern breakwater and a flushing reservoir to the north. The Kidwelly and Llanelli Canal had not yet reached the harbour and at first the main links were a tramroad from Pemberton’s New Lodge Colliery and one from Bowser’s Cwm Capel. The beginnings of the new harbour were not straightforward. Bowser and Pemberton skirmished for priority in their shipping and the facilities were inadequate when the opening was announced in 1832. Despite the qualification of the engineers the quality of the work was such that sections of the walls collapsed, suggesting that a combination of the rush to open for shipping and the unstable nature of the ground was responsible.

The second phase in the process of building the new harbour involved the appointment of engineer James Green by both the canal and dock companies as a consultant engineer. His contribution was to produce a new and ambitious plan for the docks linking in to the canal network which he was suggesting. Green’s vision was to bring the largely derelict Llanelli and Kidwelly Canal to the harbour in Burry Port and extend it further up the Gwendraeth Valley to take advantage of the superior coal in that region. The pivotal harbour development was his plan for a large floating dock which would incorporate the existing scouring reservoir. The Llanelli and Kidwelly Canal would be extended to link with the dock and the tramroad from Llanelli to Pwll would also be extended to provide a continuous tramroad from Llanelli to Burry Port. Following the failure of the walls of the flushing reservoir James Green was dismissed. However, it is not clear whether this was the result of his design or simply poor workmanship and a rushed job. RE Bowen notes that “the fickle finger of fate pointed towards James Green, perhaps somewhat unfairly”.

The third phase reflects the ambitious nature of Green’s plan, influenced perhaps by his schemes at Cardiff and Newport docks. Clearly, despite the future promise of sustained shipping inherent in Green’s vision, the scheme was not viable. R.E. Bowen surmises that what emerged after consideration by the company was a reduced size dock presumably built in accordance with new plans from Sir Edward Banks and probably constructed under the supervision of William McKiernon.

JAMES GREEN – HERO OR VILLAIN

Reviewing his achievements in Devon and Burry Port, these are some conclusions:

- His reputation as a civil engineer was excellent and most of what he was involved in was very successful.

- His achievements in Devon were outstanding in that he replaced or improved many of the original 236 bridges with structures that have lasted until now.

- His work as a canal engineer in Devon is regarded as innovative and largely successful. The use of tub boats and inclined planes was a clever and largely effective way of avoiding the large costs of installing locks.

- Building a large mansion and a church, reclaiming land, and improving roads in addition all his other work is remarkable.

- Working both as an engineer and contractor on projects and taking on work outside Devon which involved much travel may have affected his efficiency. Many suggest that he spread himself too widely.

- The failure in the harbour wall at Burry Port in 1832 cannot be attributed to Green since he was not involved at that time, but he has to accept some responsibility for the crumbling of the walls of the scouring reservoir even though other issues may have caused the problems.

- His miscalculations of the cost of completing the inclined planes of the Llanelli and Kidwelly Canal delayed the project certainly, but since it was eventually completed the design must have been sound.

Overall, the vision, innovation and technical brilliance of James Green must make him one of the pioneers of the integrated harbour, tramroad and canal network which defined Burry Port from the 1830s onwards.

GRAHAM DAVIES December 2023