GWYN ROWLANDS – A TRAGIC STORY

I’ve often looked at the war memorial in Burry Port and wondered about the people named on it. How old were they? What did they look like? Were they married with families? What did they think about the wars in which they eventually died; a sense of adventure, a feeling of fear and dread, or a mixture of both? I know the story of one of the people named and I thought I’d share it.

The photo on the left shows, in 1908, the Rowlands family of 17 New Street, a house the family owned and occupied from about 1900 until the early 1980s. In it are the mother, Margaret, her mother and seven of the children, three more were to come. The father, David Rowlands, is absent – he’d recently made, along with other local men, the huge land journey to work in Russia. Standing between his mother and grandmother is the second son, John Gwynfor – Gwyn – aged 8 or 9.

David Rowlands was very much against the first world war. He saw it, like many did and still do, as a capitalist war between empires over money and power. He wanted his sons to have nothing to do with it. Idris, the eldest, was a coal miner and therefore exempt from service, the youngest ones weren’t old enough, and David advised Gwyn not to volunteer. However, when an army of volunteers was massacred because of idiotic tactics in the Battle of the Somme of 1916, conscription was introduced and, in 1917, Gwyn was called up. David, who had followed the war closely, persuaded Gwyn to try to get into the M.G.C, the Machine Gun Corps. He dreaded his son going ‘over the top’ to almost certain death, and theorised that he had more chance of survival in the M.G.C which, being dug in and mainly defensive against German attacks, would probably be slightly less dangerous. And that’s what Gwyn did.

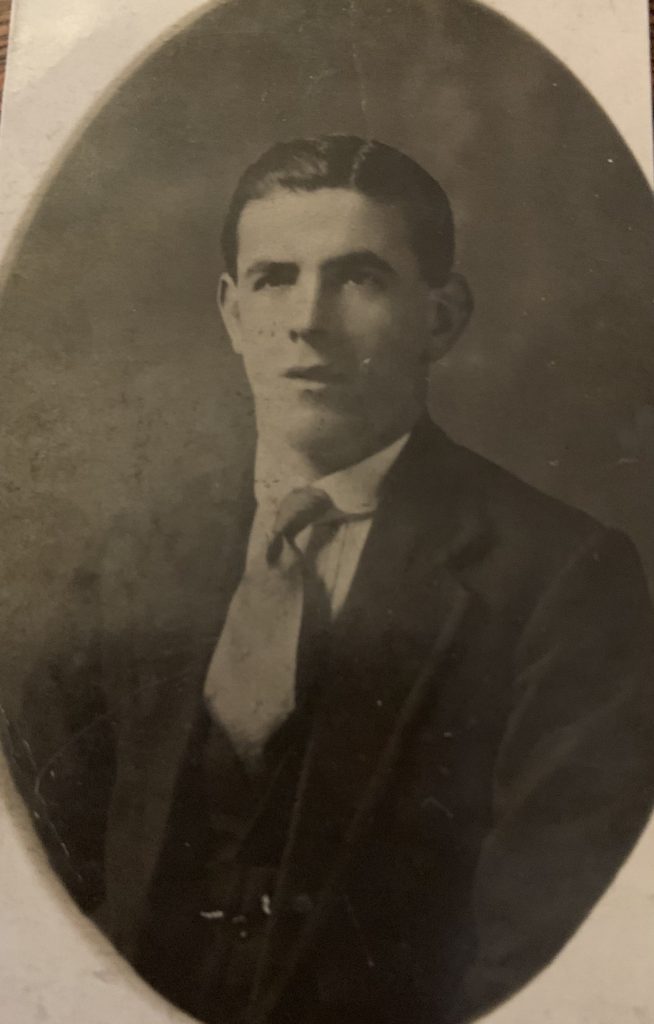

Gwyn had an especially close bond with his youngest sister Agnes. They would talk for hours, and Agnes would always remember his sense of humour, his infectious laugh, and his bright blue eyes. He had a girlfriend and often said he planned to marry her when the war was over. On the day he left New Street for the last time he said to his mother in front of six year old Agnes, in Welsh of course, ‘Look after her until I get home’.

The photo on the left is of Gwyn, front middle, with other M.G.C members in his unit. It took at least four men to handle one of these guns. On March 21st 1918, with American troops and resources now arriving every day on the allied side, the Germans began their ‘Spring Offensive’, a last desperate attempt to win the war on the Western Front. It nearly succeeded – they made huge advances until a shortage of equipment stopped them. The Allies then counter attacked successfully until the war ended in November.

The March offensive began with a bombardment. Reconnaissance planes had pinpointed the machine gunners, and Gwyn’s unit was hit, killing them all. There was nothing recognisable left, and the body parts were buried together, somewhere, unmarked.

I know this because one of the unit survived and told David what happened. This was Gwyn’s best friend, David Randell Lewis -Dai – of Pembrey, back left in the photograph. On that morning, Dai had toothache, and was allowed to go behind the lines to have the tooth removed. He was teased by his mates as he left, and when he returned, an hour or so later, there was nobody left to find. David’s children somehow heard the story too but, at David’s insistence, not Gwyn’s mother Margaret. For the remaining twenty years of her life she wore black and never left the house, always believing that Gwyn had a marked grave somewhere in France. In fact, his name appears on a monument there to soldiers with no known burial places.

One can only speculate about how, in those days without medication or counselling, Dai coped with the trauma he must have suffered. After the war he visited Gwyn’s mother every week. In the late 20s, he twice won the Welsh amateur golf championship and played for Wales many times. In those days, Welsh golf professionals were simply shopkeepers, therefore, for some years, Dai was unquestionably the best golfer in the country. He eventually became the professional at Ashburnham, where a trophy in his name is still played for today.

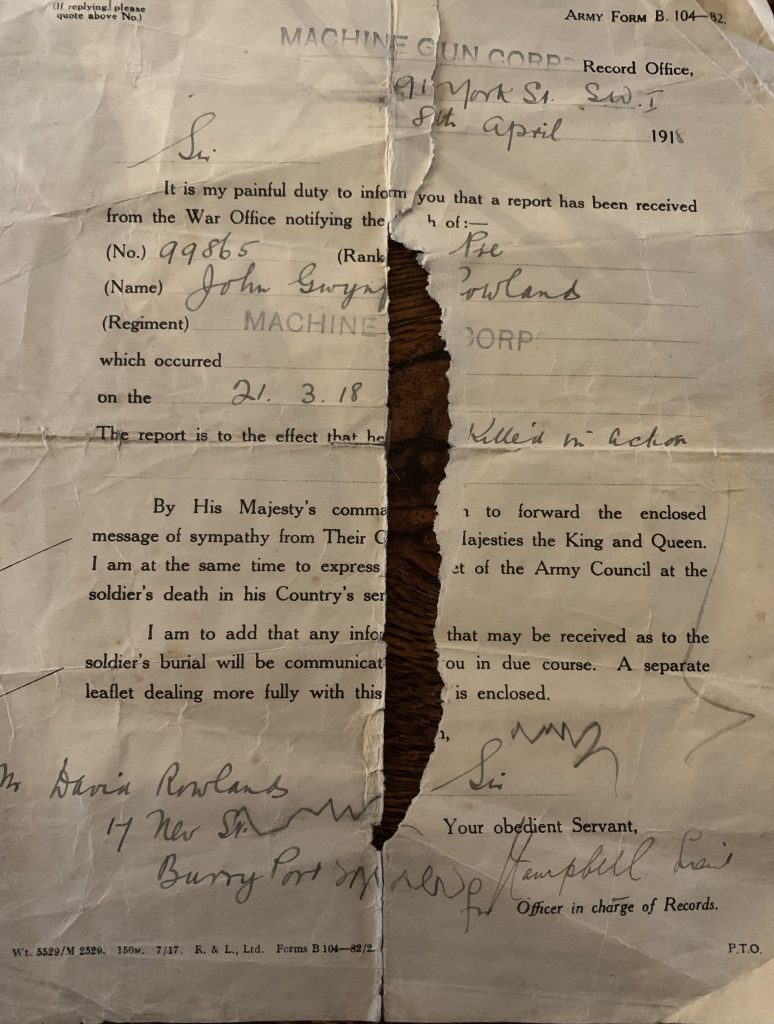

The photo below is of a document I recently found, folded away in a box, possibly for over 100 years. It’s the form David and Margaret received informing them of Gwyn’s death. I’d always assumed families received telegrams, I’ve found out however that in 1918, and possibly throughout the war, telegrams were reserved for families of officers, not privates like Gwyn. This ‘Form B 104-82’ is dated April 8th, and of course would have taken some time to arrive, so Gwyn’s family would not have heard of his death until around a month after it happened. It’s a strange feeling to possess a piece of paper knowing that, when Gwyn’s parents (my great-grandparents) first held and read it, it broke their hearts.