THE WORKERS IN THE EARLY INDUSTRIES

In the first coal mines men would dig out the coal from the surface on higher ground so that the water could drain away. The coal would then be taken to a nearby shipping point on carts and later tramways, railways and canals. However, the industrial revolution demanded large quantities and with the invention of the steam engine water could be pumped out and deeper pits sunk. Alexander Raby’s new pits depended on a pumping engine. Yet as mining became more expansive so did the dangers for the miners underground. Symons describes the laxity in the reporting and reluctance to acknowledge the growing number of accidents resulting in injury and death, mostly as a consequence of neglect, apathy, lack of investment and poor management by the owners.

The reported causes of deaths in the coal industry in Llanelli in the middle years of the 19th century were mainly from falls of stone, coal or earth in the workings, accidents at the top and bottom of mine shafts and explosions of methane (firedamp). Children, some as young as five, were used in Llanelli’s collieries for opening and closing the air doors and drawing the ‘corves’ by straps around their shoulders and waist. It was desperate poverty that made it necessary for families to allow their children down the mines, and, although the 1842 Mines and Collieries Act banned all girls and women and boys under 10 from working underground, this continued until the 1870s.

Alexander Raby was popular and he was said to pay his workers well. But when iron master Robert Crawshay had the words ‘God Forgive Me’ carved on his tombstone it was undoubtedly to do with remorse for the misery of a hell on earth his family had brought to generations of iron workers in Merthyr. What a writer in 1884 described as “great towers of brick work, filled with burning coal or coke, melting limestone and fluid iron … perpetually vomiting flame and Stygian smoke…” did not do much for the health of the workers employed by the iron masters. They lived in luxury while workers often lived in poverty with poor water supply and inadequate sanitation. Children and young people were employed in the works filling the barrows with iron for the forge, breaking up limestone, filling up the boxes with coke at the furnace, cutting up scrap iron for the furnace, taking the cinders from the furnace.

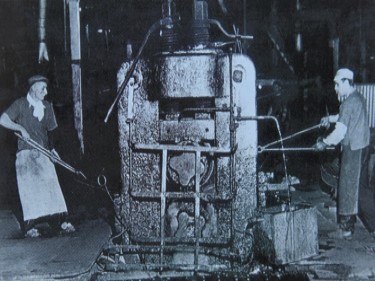

The tinplate workers in Llanelli and Burry Port worked in very harsh conditions. One writer described the hot of the end of the works: “The heat was infernal, the fumes insufferable, the noise stupefying. Screaming-hot jagged edged plates, arcing through the air on long tongs or skidding along the iron-surfaced floor, caused burns and crippling lacerations.” People worked in dangerous conditions in temperatures up to 38°C and men would drink up to 40 pints of liquid during an eight hour shift. Workers provided their own protective clothing or face horrific injuries. Tinplate might employ whole families at various stages of their lives and young people as young as 13 years. Heavy working in poorly ventilated spaces and the primitive sanitation facilities led to workers facing a future of respiratory diseases, rheumatism and other diseases and the average age at death was 45 years.

The copper works owners in Llanelli and Burry Port generally looked after their workers, providing housing and education and copper working was often regarded as the ‘aristocracy of labour’ with comparatively good pay and largely cordial owner-worker relationships. Yet the work was hard and often dangerous and workers might work a 24 hour shift. Noxious fumes were a constant irritant and chronic bronchitis and asthma a common consequence. The furnace man was exposed to the heat of both molten metal and the stream of slag and sometimes spills and splashes caused terrible scalding. Children as young as eight were known to be used and these might work from 6 am to 8 pm. Women and girls broke ore into small lumps and wheeled coal and ore to the furnaces. Boys cleaned ash-pits and greased machinery, wheeled coal and ore to the furnace and took ashes from it, and broke up the slag to find copper for re-melting.

Unsurprisingly from what we have described, industrialisation was accompanied by social unrest and rebellion. In Wales the most discussed examples tend to be the Chartists, Rebecca Riots and Merthyr Riots. But that is another story.

GRAHAM DAVIES May 2022