The Beginning

One morning, in the early months of 1881 a group of individuals looked out over the vast dune system at Pembrey. The gentlemen concerned represented the Stowmarket Explosives Company of Suffolk. They had found the perfect spot to construct a Powder Works for the manufacture of explosives.

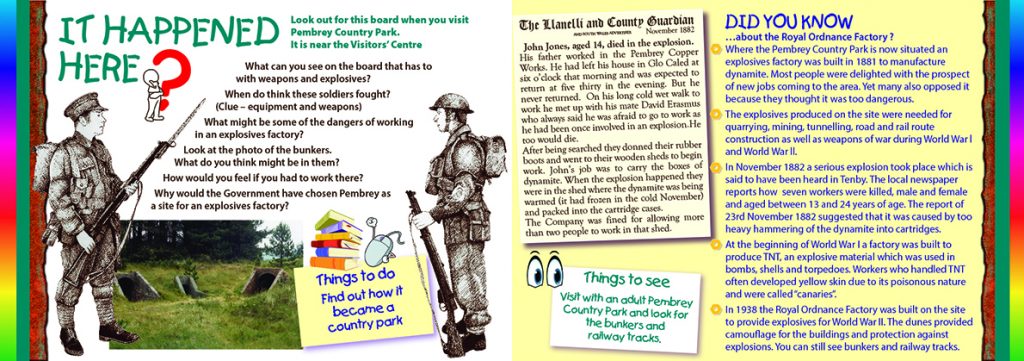

In June of 1881 it was reported in the local press that a Powder Works was to be established within what is now Pembrey Country Park. The majority of the local population were delighted with the prospect of new work coming to the area; however, many were also opposed, because of the dangerous nature of the product.

Owing to the demand for explosives, mainly for quarrying, mining, tunnelling, road and rail route construction, the company soon started building the works. In order to get materials for construction brought quickly to the site, shipping had to be relied on, as at that time the road transport network was far from today’s standards. They took over a lease for Pembrey Harbour, which had been closed for some years due to silting and the company succeeded in dredging a channel 80 feet wide.

To get materials to the site of the Powder Works the company had constructed a narrow gauge railway from the harbour. Its engine, called the ‘’Rocket’’, drew its water from a well which used to be sited in the garden of the Harbour Masters house. The building works were so advanced by June 1882 that many construction workers had already been dispensed with, and it was announced production would start soon.

Explosions

Shortly after production began, on November 11th 1882 there was a minor explosion at the works. As nobody was injured the Company assured the Home Office that production procedures and safety precautions were of the highest standard so no further action was taken. Llanelli MP Sir John James Jenkins questioned the Home Secretary in Parliament regarding the adequacy of safety at the site, asking if he was aware of 300tons of explosive being stored in a shed only licensed to hold 150tons!

The following day, on November 17th, a violent explosion occurred in the works which is said to have been heard in Tenby. Seven workers were killed, male and female, aged between 13 and 24 years of age. The next day the Coroner had 16 men sworn in as jurymen at the Ashburnham Hotel. Questions were put to victims’ relatives in order to gain some background knowledge. It was found that some of the unfortunate victims could not read or write but others were able to do so in Welsh and English. They were told that John Jones used to leave the house for work at 6.00am and return by 5.30pm. He was 14yrs of age. He earned what would equate today to 6 1/2p a day.

The girls would generally earn more than the boys as a lot of their work was based on piece work rate. This in fact caused quite a crisis for some of the well to do of the area. Domestic servants were more or less impossible to find as wages were much better at the Powder Works.

The inquest found the cause of the explosion to be due to some ‘’larking about’’ but a sum of £150 was to be shared amongst relatives in proportion of one years wages for each victim.

At this time employees numbered 72, half of these female. Workers of the day were searched on entry for inflammables and anything which could cause a spark. India-rubber over boots had to be worn, no hair pins were allowed and women were strictly forbidden from wearing stays containing iron or steel.

No exposed iron was to be found in the works, heads of nails used in construction were all covered with putty. Floors were of sand and huts lightly built to give little resistance if an explosion occurred. Also, the rules governing workers were read to employees once a month.

WW1 Period

In October 1914 Nobel’s Explosive Company Ltd. of Glasgow agreed with the Secretary of State for War to erect and manage a T.N.T. factory on the site of the industrial explosives factory. Nobel’s Explosive Company would only have to pay three-tenths of the capital expenditure; the State would cover the rest. The Company was also under an agreement to manufacture propellant explosives for the Admiralty. In May 1915, a separate loading factory was built for the filling of shells, mines and torpedoes. The state would cover the whole of this cost. It was agreed that Nobel’s company would operate the factories which became nationalised and owned by the Ministry of Munitions.

The factory buildings were arranged in a progressive order. Raw materials, stores and acid plants were all convenient to the internal ‘’spiders web’’ of railway lines. A safety zone of 400 yds. lay between the T.N.T. and propellant explosives section and was kept free from buildings.

The factories were completely self-contained with their own boiler houses and power station. Water was piped from the Gwendraeth Fawr and Fach to an underground reservoir where it was chemically treated, filtered and pumped to high level storage tanks – the daily consumption of water was 4,000,000 gallons. The factory power station had 7 generators and the site had 4 boiler houses.

In July 1917, a huge explosion occurred at the Pembrey factory. It became nicknamed ‘’the Hill 60 explosion’’ after an explosion at Ypres. Owing to wartime restrictions there was no immediate press report about it even though 6 people were killed. The inquest was held in Llanelli on 21st August 1917. The verdict of the Coroner was ‘’the deceased were accidentally killed by an explosion due to some unknown cause’’.

Two of the six killed were Mildred Owen (18) and Dorothy Mary Watson (19) from Swansea. Their funeral was attended by many workers from the Munitions Factory and they walked in procession, alongside the hearse, through Swansea to the graveyard. On the War Memorial at Swansea the names of Mildred and Dorothy are among twelve other people who were killed in various other factories.

The work itself could be hard, repetitive and also harmful. Above the door of the Employment Office at the factory was a sign: ‘Blondes need not apply’. It was thought the skin of those with a fairer complexion would not be suitable for the harsh chemical environment of the munitions production process. Personal protective clothing was nowhere near what it is today and dealing with nitric and sulphuric fumes and solutions was hazardous. As well as T.N.T. and Cordite to deal with, it was no wonder skin, hair, eyes and lungs suffered.

Women working in the industry carried a nickname of ‘’the Canaries’’. It was because they suffered with a toxic jaundice due to chemical contact and breathing toxic fumes. Their skin and the whites of their eyes would become a yellowish colour due to the illness. For those working in production areas containing nitric or sulphuric acid fumes, the breaking down of tooth enamel was also a problem.

The fact that the workers financial remuneration was good,(once again the girls on piece work earning more than men), there was a supply of good hot food at works canteens and a clean uniform every day must have been an overwhelming attraction.

WW2 period

In 1938, the Government decided to re-establish a Munitions Factory at Pembrey. This Factory was known as the R.O.F. – The Royal Ordnance Factory. Smaller in size it was a far more efficient production unit and comprised services and facilities more akin to a town rather than a factory.

There was a magnificent Central Office which housed draughtsmen, laboratory staff and senior management and a well-equipped Police Barracks which also housed an armoury. Other buildings comprised of a superb main canteen, a surgery housing a team of doctors and nurses who would attend to workers’ medical needs as well as a library with a sports and social clubhouse. A super efficient laundry was on site to provide the necessary daily clean uniforms.

Production here started in December 1939 and Pembrey soon became the largest supplier of T.N.T., Tetryl and Ammonium nitrate. The whole factory was enclosed by a high boundary fence, patrolled by the War Department Constabulary. They also ensured that no worker would enter his place of work possessing matches, cigarettes, tobacco or pipes. Any food or confectionary brought to work would have to be deposited at the main canteen. This regulation is due to the fact that certain foodstuffs, e.g. sugar, can act as a catalyst to many chemical reactions used in the manufacture of explosives.

On the night of November 1st 1941, an air raid alert was in progress. As was customary in such a situation, acid feeds were cut off and workers retired to shelters. In a unit called P14, due to the thermometer in this mono-nitration plant needing to be read every 5 minutes, a person would leave the shelter to carry out this essential check. After the air raid alert everything seemed normal and production continued. Assistant foreman E.B.H. Williams, who was near P14, then heard a huge explosion. He saw the roof had been blown off and the remaining building alight. He immediately accessed a platform outside the building and turned off the acid and toluene tank valves. Williams then entered the building with Fireman H.J. Gurr. One worker had been blown out of the building, others came running out with their clothes on fire. Two of them, W.M. Evans and C. Bowen died shortly afterwards. Williams then made his way to 3 more nitrators which were still a potential source of danger. He went inside these buildings and closed all the valves. Mr. Williams and Mr. Gurr were each awarded the British Empire Medal.

At maximum output over 3,000 worked at the R.O.F but after WW2 there was a reduction down to 1,000. Its main function became the dismantling and washing out of surplus munitions. The factory also utilised many bi-products such as ammonium nitrate which was sold as an agricultural fertiliser. T.N.T. flake bags, after decontamination at the laundry, were dispatched to be converted into paper for production of banknotes. ‘’Carbon black’’ from waste T.N.T. was used in commercial manufacture of printers ink.

On the 14th December 1963 the Ministry decided to put the R.O.F. up for sale and it was eventually bought by the old Llanelli Borough Council. This eventually enabled Pembrey Country Park to be established, but not without a few threats to the site.

DAVID HUGHES

(Based on his article in ‘Llanelli Miscellany’, Number 29, 2016)